by Terry Messman

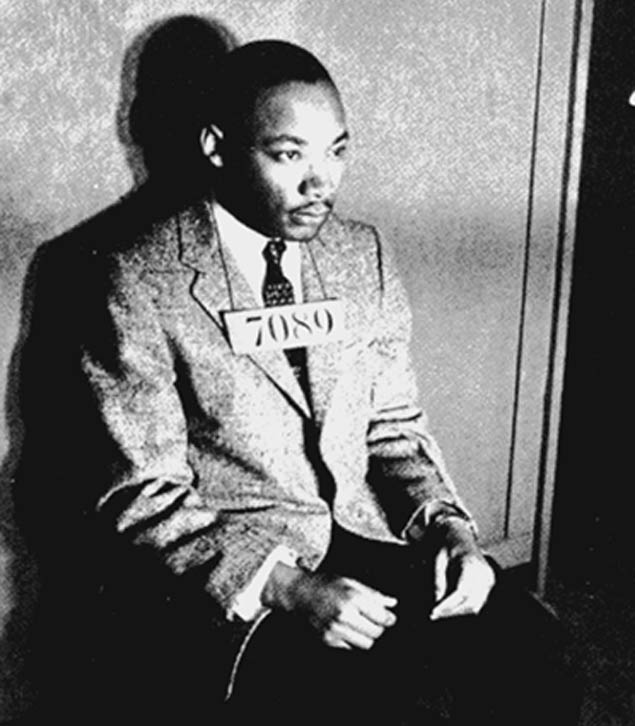

[dropcap]V[/dropcap]incent Gordon Harding began working closely with Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Freedom Movement in the early 1960s as a nonviolent trainer and activist who was arrested in the struggles to overcome segregation and racial discrimination.

An eloquent speaker and writer, Harding also was a peacemaker, and his early — and prophetic — condemnation of the Vietnam War was a crucial influence in inspiring King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to take a bold and uncompromising stand against the war at a moment in our nation’s history when it mattered most — and was most controversial.

Harding arrived at our interview on April 23 wearing a button conveying a stark insight: “War is Terrorism.” The small button speaks volumes about the long-standing faithfulness of a man who still carries on his commitment to peacemaking and nonviolent resistance to America’s present-day war machine, even though it is now 60 years since he became a conscientious objector as a young man in his early 20s, while serving in the U.S. Army from 1953-1955.

He is still upholding his witness for peace some 46 years after he was asked by Martin Luther King, Jr. to write the first draft of one of the most momentous speeches in U.S. history, King’s “”Beyond Vietnam” speech, delivered on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York. The speech was a prophetic call to end U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War — an outspoken cry for peace that was literally heard ‘round the world.

Dr. King had already been speaking out against the war, and turned to Harding to draft this eloquent anti-war speech because the two men shared deeply held moral and philosophical convictions about the injustice and cruelty of the Vietnam War. King essentially delivered Harding’s words that day with only a few modifications. It turned out to be one of the most controversial anti-war speeches in modern U.S. history, and ignited both a firestorm of criticism and an outpouring of support.

At the time of King’s Riverside speech in 1967, Harding already had thought about the issues of war and peace for many years. After becoming a conscientious objector in the 1950s, he became involved in the Mennonite Church, one of America’s historic “peace churches.”

Harding and his late wife, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, moved to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1960 to participate in the Southern Freedom Movement as representatives of the Mennonite Church. Vincent and Rosemarie founded Mennonite House, a gathering place for movement activists in Atlanta, and traveled throughout the South in the 1960s, working with King and the SCLC in the freedom struggle as activists and nonviolence trainers and teachers.

Almost from the very beginnings of his life as an activist, Harding understood the deep connections between working for peace and seeking racial and economic justice. He was dedicated to challenging discrimination and segregation, while simultaneously working for peace and nuclear disarmament.

In the early 1960s, peace activism was still relatively rare in the United States, yet Harding’s two-fold commitment to ending war and overcoming segregation already was evident in the summer of 1962. That year, Harding became involved in the Albany Movement, a broad-based campaign of nonviolent resistance aimed at overturning the segregation laws in Albany, Georgia, and he was arrested for leading a demonstration at Albany City Hall in July 1962. Only two months later, in September 1962, he also was active with the Greater Atlanta Peace Fellowship in protesting the nuclear arms race.

Today, Harding continues to illuminate the connections between seeking peace and working for social justice. He has written eloquently about how Martin Luther King was dedicated to simultaneously resisting the “triple evils” of racism, militarism and economic exploitation.

Freedom Movement’s legacy

The Southern Freedom Movement left an enduring legacy in its valiant campaigns to overcome a brutal and seemingly all-powerful form of segregation that Harding unhesitatingly calls a “terroristic system” of violent subjugation.

Nonviolent activists not only made history by challenging the brutal system of racial oppression in America, but the Movement’s legacy extends far beyond the struggle for equal rights, and reaches far beyond the shores of our own nation.

In his book, Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement, Vincent Harding describes vividly how the legacy of the Freedom Movement has transcended its era and transformed the world.

In 1989, as Chinese students occupied Tiananmen Square in Beijing as part of a nonviolent movement for freedom and democracy in their country, they constantly displayed the unforgettable words of the Freedom Movement’s own anthem, “We Shall Overcome” — words that Harding and thousands of his fellow activists had sung in countless marches for justice.

Those three powerful words that had expressed so well the heart of a generation’s courageous struggle for freedom in America were now giving strength to a struggle for freedom decades later and thousands of miles away, in China.

“We Shall Overcome.” Those three words were displayed defiantly on many banners waving above the demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, were imprinted on shirts bravely worn by protesting Chinese students, and were declared boldly on leaflets that voiced the ideals and hopes of this democracy movement.

The electrifying message of a movement originally born in the oppressive heat of terribly costly human rights struggles in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee, had now leapt across the oceans and, ignoring all barriers of time and distance, had miraculously galvanized other hope-filled freedom movements in such far-flung countries as China, South Africa, the Philippines and Poland.

For many veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement, it was an experience of amazing grace to see the inspiration of their home-grown movement ignite the hopes of millions of people waging crucial struggles for freedom overseas.

In his book, Hope and History, he wrote: “The Chinese students seemed to be saying that they recognized and were inspired by the power of our African-American struggle. Their signs were new evidence and confirmation for us, if we needed it, that this American freedom movement of the post-World War II period was no relatively narrow contest for the ‘civil rights’ of Black people alone, important and endangered though those rights were and still are.

The life-risking students in Tiananmen Square were claiming our movement for what it really was: an epic, life-affirming, nonviolent struggle for the expansion of democracy, a great contribution to the twentieth century’s movements for human renewal and social transformation.”

More than civil rights

The Freedom Movement launched by African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s now had become a shining lesson for the whole world. That is one reason why Harding continues to stubbornly insist that naming this epochal struggle for freedom and democracy “the civil rights movement” does not do full justice to what was truly at stake.

Instead, he has long described it as the “Southern-based, Black-led, Freedom Movement,” because it had more far-reaching goals than simply winning legalistic victories to protect a narrowly conceived notion of civil rights. As Harding explained in our interview, the full measure of what was really at stake was captured far more evocatively in the words of another of the Movement’s powerful anthems: “Woke up this morning with my mind stayed on freedom.”

As Harding continues to think and teach and write about this momentous struggle for freedom, he has gone beyond his own formulation, and now sees the Movement as nothing less than an historic effort to expand and deepen democracy for all people. Perhaps that helps explain why this movement has so much power to inspire activists all over the globe as they struggle to deepen freedom and expand democracy in their own countries.

As a scholar, university professor, theologian and author, Harding has now devoted much of his life to teaching about the meaning of the Freedom Movement. His insights into the very heart of the Movement are as meaningful for activists today as they were during the struggles for freedom in the 1950s and 1960s in Birmingham, Montgomery, Albany, Selma, Chicago and Washington, D.C.

After Martin Luther King’s assassination, Harding worked with Coretta Scott King and was named as the first director of the Martin Luther King Jr., Memorial Center. He also served as senior academic consultant to the highly acclaimed PBS television series on the history of the Freedom Movement, “Eyes on the Prize” and “Eyes on the Prize II.”

Harding taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Spelman College, Swarthmore College, and Pendle Hill, a Quaker study and retreat center, and then taught theology at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver from 1981 to 2004.

Harding is the author of several influential books, including There Is A River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America, a seminal study of the long decades of struggle by African Americans to overcome slavery and keep their dreams of liberation alive. Harding also authored two illuminating reflections on the meaning of the Freedom Movement for today’s struggles against injustice: Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero, and Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement.

In these books, Harding describes King’s deepening dedication to the radical transformation of our society, a journey that led far beyond the March on Washington in 1963 when Martin captivated the nation with the soaring eloquence of his “I Have A Dream” speech.

A truly prophetic figure

In the final months of his life, in 1967 and 1968, King had grown into a radicalized and truly prophetic figure who had committed himself heart and soul to fighting the “triple evils” of militarism, racism and economic exploitation. In publicly opposing the Vietnam War and in his courageous attempts to build a Poor People’s Campaign, King had set out on a showdown with what he was now calling “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world” — the federal government. It was a costly decision and a fateful journey — one that ended in his assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968.

In The Inconvenient Hero, Harding confronts readers with that prophetic and revolutionary Martin Luther King who had made what he calls “an essentially religious commitment” to the poor at home and to ending the war in Vietnam.

In simple words that are nonetheless among the most profound and prophetic words I know, Dr. King described his vision of solidarity with the poor in 1966.

King said, “I choose to identify with the underprivileged. I choose to identify with the poor. I choose to give my life for the hungry. I choose to give my life for those who have been left out of the sunlight of opportunity…

“If it means sacrificing, I’m going that way. If it means dying for them, I’m going that way, because I heard a voice saying, ‘Do something for others.’”

That is who Martin Luther King had become: A man who was, at one and the same time, a pastor, a prophet and a nonviolent revolutionary.

The preacher and the empire

Harding’s writings offer important insights into King’s startling growth into something far more revolutionary than the dreamer of 1963. Now, he was the preacher who would bring down an empire, the radicalized King who still believed in the dream of equal rights for all, but who had shown the steely resolve to take on poverty, slums, hunger and the Vietnam War.

In his last year on earth, King had become a man of destiny with a burning drive to confront the federal government in a showdown in Washington, D.C., and force government officials to hear the cry of the poor for justice.

That is why the Street Spirit interview began by asking Harding to reflect on the final year of his friend’s life on earth.

I interviewed Vincent Harding on April 23 while he was visiting the Bay Area with his “beloved” Aljosie Aldrich Knight, in his words. Harding responded to every question by first closing his eyes and remaining in contemplative silence, then thoughtfully answering with beautifully articulated reflections that seemed to come from some deep place within.

Street Spirit is grateful to nonviolent activists David Hartsough and Sherri Maurin for their generous help in arranging the following interview.

At the end of the session, David Hartsough said in gratitude that the interview had been “profound.” Harding’s reflections were, in fact, a profoundly insightful meditation on the heart and soul of the Freedom Movement, then and now.

[typography font=”Cardo” size=”14″ size_format=”px”]To read Terry Messman’s full interview with Vincent Harding click here.[/typography]