by Terry Messman

While filming the long, winding wanderings of homeless recyclers through the streets of Oakland, Amir Soltani and Chihiro Wimbush, co-directors of Dogtown Redemption, began to wonder when the redemption named in the documentary’s title would take place.

The redemption at the heart of the film is not the mere act of redeeming bottles and cans at Alliance Metals in West Oakland. It is the redemption of lives and souls — the redemption of humanity crushed and battered and buried in the earth.

While the film provides a fascinating exploration of the politics of gentrification and homelessness, and defends the human rights of recyclers targeted for removal by duplicitous city officials acting on behalf of an intolerant public, an issue of far deeper significance soon takes over the very heart and soul of the film — the redemptive love and friendship that rises on the midnight streets of West Oakland.

Dogtown Redemption is shot through with unexpected moments of transfiguring grace, ranging from shattering breakdowns to electrifying moments of joy. It is a film that asks unanswerable questions about the very meaning of existence, and reflects on both the saving grace of love and the bitter injustice of death.

That may seem like an exalted claim to make for a down-to-earth film about homeless recyclers who rummage through discarded trash. It is not.

Rahdi Taylor of the Sundance Institute offers an assessment of Dogtown Redemption that hits the point exactly: “There is love in every frame. The kind of unconditional love of family; the love that accepts you exactly as you are and exactly as you’re not, and loves you anyway.”

Heart-shaped cinema

This is cinema in the shape of the human heart. At some indefinable point, right before our eyes, this film skips the rails, and a documentary about recycling transcends all the politicized issues at stake, and becomes a glimpse into the heart of the human condition.

The journeys of Landon Goodwin, Jason Witt and Hayok Kay are carried out on garbage-strewn streets, yet they have the sweep of The Odyssey on the streets of Oakland. Like Ulysses, these wanderers left their homes for years on end and are exiled on endless voyages through a landscape of deprivation and despair.

Their lives are alternately broken apart by despair and redeemed by love. In the seven years covered by this film, they will be maligned by an intolerant public and by unjust city officials. All three will be beaten brutally on the streets — by different assailants, yet by the same criminal indifference of society to their plight.

Before the film ends, each of the three wanderers and some of their closest friends will pass through the valley of the shadow of death. Some will live to see another day. Others will never be seen again, except in memory.

Moments of love and redemption take place in each one of their lives.

We witness the joy felt by Jason Witt, a battle-hardened survivor of the streets who has been forged into recycled steel after a lifetime of hard blows. Yet he is greatly moved by the outpouring of love and affection from his teacher and brothers at the Contra Costa Budokan where he earned a black belt in the art of the samurai sword. In an unforgettable close-up, the face that seemed to be made of unbending iron softens and the steely eyes well up with tears of gratitude.

We witness the haunting final days of Miss Hayok Kay, a kind and generous homeless woman who was dearly loved by so many friends on the street, and also loved by the film’s directors, Amir and Chihiro, who were so captivated by her spirit that they became personally involved in trying to preserve her life.

Miss Kay is undone when her true love and best friend dies a homeless death, and she is then broken down piece by piece by the brutality of the streets. Yet we are privileged to witness this woman’s heart as she sings “Stand By Me” at a memorial for homeless people in Oakland. It is a song for the loves and losses in our lives.

The minister of the recyclers

Yet, the finest image of redemption takes place in the life of Landon Goodwin, a homeless recycler Amir Soltani describes as “the minister of the recyclers.” Landon calls forth the courage and heart to uplift himself from a life of poverty and substance abuse, enters a rehabilitation program, and prays for the strength to get off the streets.

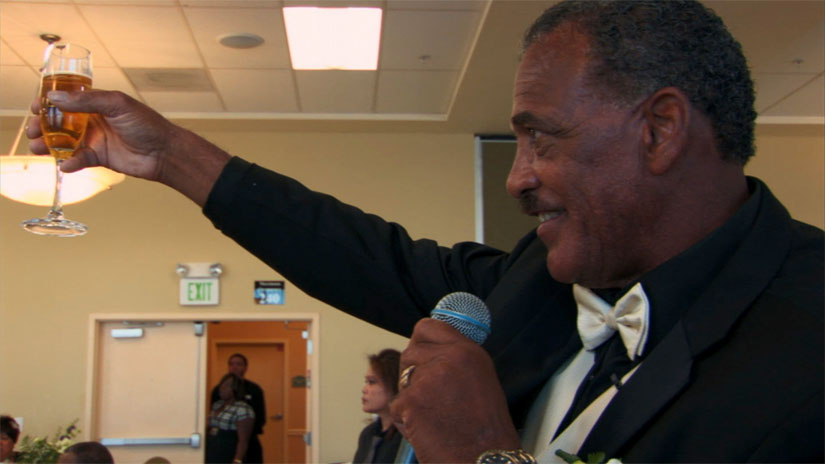

At the end of the film, it’s impossible not to cheer at the sight of Landon walking down the aisle with his bride Suzette Anderson. It can’t always happen in life, but it feels so right when every once in a while, against million-to-one odds, a fairy tale jumps right out of the pages of the storybook and comes alive to enchant us.

That storybook ending didn’t happen in Hollywood. These moments of miraculous hope and devastating despair all took place in Dogtown USA, an area of West Oakland supposedly named for the large numbers of stray dogs on the streets in years past. West Oakland, the place where our brothers and sisters languish in poverty, and live and die on the streets, is also the place where dreams of redeeming grace sometimes beat all the odds.

In the end, those moments of love and humanity in Dogtown Redemption beat down the rotten injustices of Oakland’s municipal officials and the soaring national poverty rates, the staggering rents and the cruel slumlords and evictors.

All that injustice momentarily fades away when an underdog hero emerges from the streets, puts on a wedding coat, walks into a church, and becomes a man rescued from a life of loneliness and poverty by the love he never stopped believing in.

On his long day’s journey out of the streets of exile, Landon paid some very heavy dues before that moment when redemption walked down the aisle, smiling and radiant, to take the vows with him.

A Meeting at Midnight

For the co-directors of Dogtown Redemption, their understanding of Landon’s journey began on the midnight streets of West Oakland. Landon was one of the first people they interviewed, after they found him sleeping outside the Alliance Metals recycling center at midnight one fateful evening.

It was so dark that, at first, Amir Soltani and Chihiro Wimbush couldn’t clearly see Landon. He was just a voice in the darkness, but they were immediately drawn in by what they heard that night.

“His voice and his heart is what really took us in,” Amir said in an interview. “Landon’s voice was just the gentlest voice you could imagine. He was so thoughtful and so courtly and so scholarly. And he was so compassionate and gentle.”

Their midnight impressions of Landon were borne out in the full light of day, when they began to see him as the pastor of the community of homeless recyclers.

“Landon was literally the minister of the recycling center,” Amir said. “He tended to people. They would come to him and speak to him. He was a healer. He was a healer even while sick, always, always. And he was deeply loved and respected by people.”

When the filmmakers decided to name their film “Dogtown Redemption,” Amir said, “I kept thinking, ‘Where the hell is the redemption going to come from?’ And ultimately, it came from Landon.”

The Wedding Day

The directors filmed Landon for several years when he was lost and lonely, desperately poor and estranged from his family — and praying fervently for a better life.

After having spent so many years filming Landon’s tough life as a homeless recycler, what did Amir and Chihiro feel on the day they filmed his wedding?

“It really was like a Cinderella story,” said Amir. “It doesn’t get better than that. He rose and inhabited his dream. There was redemption.”

On top of that, Landon was the person who presided over the marriage of co-director Chihiro Wimbush to his wife Meena four years ago.

Why did Chihiro want Landon to be the minister at his wedding, I asked.

“Chihiro lived and breathed and did everything with Landon,” Amir said. “He filmed him and he loved him. They were very close. When you make a film over eight or nine years, and get to know these people for that long, there are not too many people that one gets to know that well.”

When I interviewed Landon about the true meaning of the film, he didn’t say a word about recycling or the political struggles around gentrification. For Landon, the film was about the humanity of the people in West Oakland. I realized later that he had answered as a pastor of his homeless people.

“The undercurrent of the movie is about people,” he said. “No matter what social position they are in, people have hopes, dreams and desires. People on the streets want to live a life that is as normal as anybody else, no matter what their position is. When you see people that are in that indigent position, you should never shun people like that. You need to get to know what type of person they really are. Don’t judge a book by its cover.”

The Love They Shared

After Landon left the streets of West Oakland to enter a rehabilitation program in Vallejo, he said, “I don’t miss being hassled by cops or being made to get up and move. What I do miss is the people, the love we did share for one another and looking out for one another. You find it greater in that society than you do in this society.”

It’s a remarkable statement, and it rings very deeply true. I spent many years of my life eating, sleeping, organizing and being arrested at protests with members of the Oakland Union of the Homeless. I found far more genuine love and caring with that group of homeless friends than I have ever found anywhere else.

In our interview, Landon attempted to explain why the bonds of love and friendship forged among people on the streets can grow so strong. It’s something beyond “hearts and flowers.” It’s a matter of shielding one another in the face of a hostile society.

“When people have material things, they feel that they don’t need anybody or anything,” Landon said. “But when you’re poor or indigent, then you have to really depend on people. You feel basically powerless out on the street by yourself. But there’s strength in numbers, so people look out for each other.

“We know there’s a lot of people who taunt indigent or homeless people. I know a lot of people who have been jumped on or beaten. Miss Kay is one who was brutally murdered and died in the hospital.”

Miss Kay is not alone. Hundreds of homeless people are assaulted on the streets every year, beaten or murdered, often deliberately targeted because they are homeless and seemingly powerless. All three of the main subjects of Dogtown Redemption — Jason Witt, Hayok Kay and Landon Goodwin — have been brutally assaulted on the streets of Oakland.

“Unfortunately, Miss Kay is not the only one who has died or been injured severely,” Landon said. “I knew a few people where somebody went into their camp at night and just jumped on them and stomped them and beat them or went into their camp and set it on fire. You’re out in the open and you can be a target for anybody. So we just learn to care more about one another. We’re all we have — so we better take care of what we have.”

Assaulted and Hospitalized

He himself was assaulted by four young men who beat him with a lead pipe. Demonstrating the life-and-death value of friendship for people on the street, his longtime friend Sheila Johnson came to his aid, a good Samaritan of the streets.

“She carried me out,” he said. “She helped drag me out with her little bitty self.” Landon was extremely disoriented after the assault and fell down when he tried to stand up. Johnson stayed with him while someone called 911.

“They ran some X-rays and they found out that I had a lacerated spleen and I had internal bleeding,” Landon said.

It seems strange to say, yet the hardships and trials faced by Landon Goodwin seem to reveal the way redemption can rise from the streets. The lifeline from Sheila Johnson was the first act in this saga of redemption, and the second act began when Landon was hospitalized after the beating, and met one of his cousins occupying a nearby hospital gurney.

The cousin’s brother, Rueben Baker, was the director of a program for drug and alcohol recovery in Vallejo and wanted to help Landon. This is the moment when everything began to turn around in his life. It seems symbolic that his road to healing began in a hospital after a savage assault on the streets.

In the film, Landon looks at that symbolism. “Nothing grows from a seed unless it dies first. So, you know, so I’ve been through my valleys of weeping. I’ve been out here for a while and I want to get back to some type of normalcy in my life.”

Reuben Baker was as good as his word, and drove into West Oakland to tell Landon he had a bed waiting for him. It is a sad and bleak moving day as Landon gathers his few meager belongings from his little camp in a vacant field. Many family members had not seen him in 15 years at that point. He is tired of sleeping on concrete and in makeshift homes in bushes.

“I was destroying myself out there.”

Describing the momentous change he is going through, Landon says, “Here is a person who wants to better himself again. There was a person who didn’t care if he lived or died.”

A New Life

His life has changed greatly since he left that vacant lot. Interviewed last week, he is living in Vallejo and has a steady job at Traffic Management, Inc. He is happy in his marriage and he is now a pastor trying to help others come off the streets.

“My life is great,” said Landon. “I have a wonderful, outstanding wife. She’s beautiful and she cares. I met my wife once I came out of that life.”

Landon said that from the moment he met Suzette, “I didn’t take my eyes off her. In less than five months we were married.”

Even if he needed to get off the streets, he greatly misses his friends, the recyclers and homeless people he knew in Oakland.

“I did make up my mind that I didn’t want to be in that life ever again,” he said. “But the hardest part of leaving is that you love the people and you figure if you leave, you may never see them again. But I knew that my mission was to go back.”

The film shows Landon returning to the recycling center in Oakland and inviting his old friends back to a barbecue at his home in Vallejo on the Fourth of July.

In an interview, Amir described Landon’s return. “When he went back to the recycling center, so many people would hug him. It was almost as though one of your own had made it and had come back to you — that magnanimity of him. He opens hearts, he opens minds, he opens eyes. He’s a healer.”

Landon said he “absolutely” feels a calling to help other people get off the streets. “I’m blessed. I’m a pastor and I’m still helping homeless people. Because I know that there’s pearls in the dust. They say in the schools, don’t leave any student behind. They say in war, don’t leave anybody behind. Well, we’re not going to leave anybody behind on the streets.”

Asked about the scene where Landon invites his old recycling friends to a barbecue at his home, Amir said, “He’s done that a lot. He went back and that place is a part of him. It’s a part of his community. He gave sermons at this little church next to the recycling center. Just because he pulled out, it doesn’t mean he left people behind.”

Landon said he wanted his friends to see something about home and family life that they may have forgotten. “People are not born on the streets,” he said.

“It was nice to invite them to come off the streets. Now you’re not under a freeway, you’re not sleeping under a bridge. You’re sitting at a table, you’re eating food, you’re having fun with people. It’s a holiday. You maybe plant a seed or trigger something so they think, ‘Hey, I want this too.’ That was the whole idea.”