by Robert L. Terrell

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he conservative elites who exercise definitive control over economic and political affairs in the United States may well be dangerously overplaying their hand.

Apparently uncaring and oblivious to the needs of their less fortunate counterparts huddled far below them in the working classes, they are engaged in a full-scale assault on the nation’s tattered safety net.

These wealthy elites are opposed to paying higher taxes. They block all efforts to provide universal health care. They fight against the extension of unemployment benefits and attack public employee unions. Exercising “let-them-eat-cake” ignorance, and condescending disdain for common people, they have instructed their minions in the U.S. Congress to do their best to eliminate Social Security, and possibly federal assistance to victims of catastrophic natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes and floods.

Out of touch with the vast majority of citizens because of class-oriented apartheid, they are largely clueless regarding the problems, dreams, surging passions, and emergent hostility of the tens of millions of the less fortunate citizens on the bottom rungs of our vastly inequitable socio-economic order.

The results of this profound disconnect could prove disastrous for conservative elites, who have been largely shielded up to this point by their mouthpieces in Congress, and the compliant mainstream news media. The disconnect may also prove to be the source of the largest, and most important, demand for fundamental reforms to emerge in the United States in more than a generation via the rapidly expanding Occupy Wall Street movement currently roiling civic sensibilities in 150 U.S. cities, with new occupations joining on a daily basis.

Inspiration from ‘Arab Spring’

Although the Occupy Wall Street movement is first and foremost a heartfelt response to domestic inequality, it is obviously receiving inspiration from the revolutionary transformations fueling the so-called “Arab Spring” in North Africa and the Middle East.

The major economic and cultural differences between the scene of the Arab Spring and the United States notwithstanding, there are several good reasons to consider the possibility that revolutionary activities of the sort that are deposing long-entrenched dictators and their elite cronies in North Africa and the Middle East might be launched on these shores.

Many of the economic and political problems at the heart of the turmoil currently under way in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen and Bahrain exist here in the United States. Like those nations, the United States is dominated by remote, wealthy elites who consistently manipulate politics and economic affairs in ways that undermine the best interests of the vast majority of their fellow citizens.

For domestic and global reasons, poor people the world over are finding it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. The cost of living is rising, jobs are increasingly scarce, and comfortable living wages are as difficult to obtain as assured avenues of upward mobility.

One of the most important similarities between the United States and the nations in North Africa and the Middle East most prominently engaged in fundamental economic and political transformation involves the social and economic conditions faced by young people.

In Africa, the Middle East, and much of the rest of the Third World, large numbers of young people are finding it difficult to obtain employment commensurate with their education and training. As a result, many of them have concluded that major societal reforms are in order.

The United States also has a large cohort of unemployed and underemployed college graduates. The current unemployment rate for college graduates in this nation is the highest since 1970, and it is on the rise. Some of those unemployed graduates are prominent participants in the Occupy Wall Street movement.

Dislodging the conservatives

As protests have spread beyond New York to other cities around the nation, it is becoming apparent that the nascent movement is potentially capable of producing a massive campaign of civil disobedience dedicated to taking on, and dislodging, the nation’s conservative elites.

Political spokespersons for conservative elites are doing their best to inhibit dialogue about the profound economic disconnect between their patrons and the other 99 percent of the population purportedly represented by the Occupy Wall Street movement. The conceptually primitive epithet they launch against those who directly, and coherently, address the issue in public is “class warfare.”

By making the accusatory allegation, they seem to be seeking support from the general public via the terms of an unwritten gentleman’s agreement that it is forbidden to discuss U.S. domestic problems in such a manner.

Nonetheless, the truth of the matter is that the common people in this country do not, and have never, accepted this particular mode of censorship. This fact is clear beyond question for those familiar with working-class culture. Any sampling of the literature, music and daily gab of working-class people reveals a healthy preoccupation with the great divide between the so-called haves and have-nots.

If the mainstream news media were more closely associated with working-class people, they could serve as valuable venues for facilitating dialogue between elites at the top, and the other 99 percent of the population. But that’s not what the mainstream news media are about, and that’s why they are tentative and confused regarding the best way to report on the Occupy Wall Street movement.

The mainstream news organs could “embed” journalists with the demonstrators in the same manner as they rushed to do with U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. But there is little likelihood that any of the mainstream press outlets will engage the protesters in this manner. This is largely due to recognition that accurate, intimate, unbiased reporting about the movement will almost certainly help it become larger, and more influential.

Mainstream U.S. journalism abandoned reporting from a working-class perspective many decades ago. One of the most unfortunate results is that public dialogue in this nation is unbalanced.

Fortunately, voices that have been long banished from the public arena, dominated as it has been for decades by the mainstream media, are now being distributed and shared via so-called New Media. This is as much the case in San Francisco, Chicago and New York as it is in Cairo, Damascus and Tripoli.

Wherever in the world one encounters the emergent dialogue regarding justice, human rights and peace, the inequitable division of wealth and income between elites and everyone else is a prominent part of the agenda, and is virtually always considered one of the most important problems. Those who address this issue don’t necessarily consider themselves to be engaging in “class warfare.” They feel they are addressing a structural economic problem that is key to the future of every kind of human society.

The brutality of Reaganomics

Here in the United States, few of those who use the class warfare epithet to stifle serious public dialogue about structural economic inequities are willing to acknowledge that the nation has been subjected to such warfare for several decades. One of the most popular terms used to describe the process is “Reaganomics.”

Other than being hard-edged and heartless regarding the needs and suffering of the defenseless, it is not a new philosophy. Rather, it is a form of brutal economic Darwinism wherein a divide is severely drawn between haves and have-nots.

Wealthy people do not need Social Security, nor do they need worry about affordable health care, or unemployment benefits. The fact that most citizens do need such programs seems irrelevant to the elites, and that’s one of the reasons why their representatives in Congress are doing everything they possibly can to eliminate them.

Thus, the political component of Reaganomics is probably best understood via the stealth effort to dismantle, or at the very least, disable, the segments of government capable of protecting the mutual best interests of common citizens.

Social Security is clearly the last, best mode of financial security available to average citizens. Without it, people will necessarily be more accommodating, and possibly subservient, to those with great wealth and power. Those who doubt the accuracy of this contention should probably spend time in any large society that does not have a system of social security for senior citizens.

Class warfare by conservatives

The United States has been the scene of an intense, class-oriented “war” for quite some time, and conservatives are the ones who have been the most combative participants. This has been the case at least since Ronald Reagan’s era.

Since that time, conservatives, in the service of elite interests, have implemented numerous social, political, legal and economic policies that have handsomely compensated the wealthy, while decimating the middle and lower classes. As a result, the wealthiest 10 percent of the nation’s citizens currently possess a larger percentage of total annual income than at any time since the 1920s. The top 10 percent of U.S. earners currently receive almost 50 percent of the income produced in the nation on an annual basis.

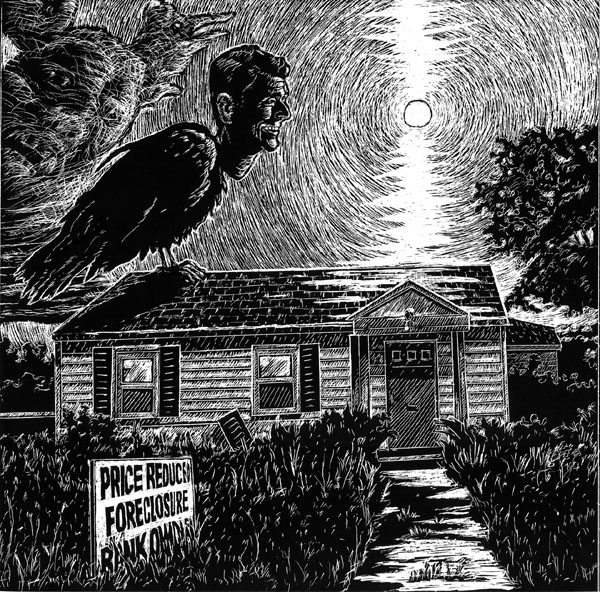

Since the Reagan era, the top one percent of U.S. earners has enjoyed a six-fold increase in income. Conversely, during that period, the other 99 percent of the population has experienced long bouts of unemployment, skyrocketing rates of homelessness, catastrophic rates of mortgage default, rising food insecurity, declining prospects for better employment and sagging home values.

The profound difference between the windfall increase in wealth accruing to elites, and the anemic economic circumstances of the tens of millions arrayed below them in the national economic pecking order, is clearly apparent in the data pertinent to income growth.

While inflation-adjusted income for middle-income earners rose 21 percent between 1979 and 2005, elites at the top experienced a 480 percent increase in income. Thus, economic inequality is undeniably at the root of the national economic crisis.

A recent report on income and poverty by the U.S. Census Bureau reinforces the point. Median household income in the United States in 2010 declined 2.3 percent from the year before, according to the report. In addition, the nation’s official poverty rate last year was 15.1 percent, up from 14.3 percent the year before.

The Census Bureau report also notes that the number of people living below the poverty line in the nation increased from 43.6 to 46.2 million, between 2009 and 2010. That constituted the fourth consecutive annual increase in the number of poor people in the nation, and the largest on record during the 52 years during which such statistics have been tallied.

Other reports from other agencies, public and private, provide similarly depressing statistics regarding the relatively rapid decline in the standard of living for tens of millions of U. S. citizens.

As a result, underemployment, unemployment and underwater are terms that have become synonymous with this deeply troubled period of middle-class decline. They are shorthand terms used to describe the social and economic carnage endured by those who are being slowly, but inexorably, pushed into desperate, degrading circumstances.

Those who lose their homes are sometimes lucky enough in the aftermath to move in with relatives or friends. But far too many end up homeless. Most often, the hapless thousands who have been forced onto the streets because they can no longer afford to pay for any sort of roof over their heads seek to survive as best they can in absolutely miserable circumstances via luck, guile, and the sporadic kindness of strangers.

Members of every age group are now experiencing stress, and frequently bewildering confusion, which results in part from recognition that those who work hard and play by the proverbial rules are no more secure than those who do not.

The fact that the vast majority of elite participants in the Wall Street excesses that engendered the current economic crisis have not been prosecuted is not lost on the tens of thousands of U.S. citizens from the lower classes who have relatives languishing in prisons as a result of criminal activities which pale in comparison with the corrupt or illegal billion-dollar schemes commonly engaged in by members of the elite banking class.

Most important, the economic and political crisis in which the nation is currently enmeshed is undermining the long-held notion that we are a nation unified via a commonly understood and supported social contract. Inherent in any such social contract, no matter the nation involved, is the basic agreement that members of society who support the law and engage in responsible work can expect to live honorable, if not wealthy, lives.

Quite clearly, this nation’s working-class people have kept their part of the bargain where our grand social contract is concerned. They have done the work, fought the wars, supported the political system, and provided private and public support for the halt, lame and indigent. Moreover, they have done this for generations.

In addition, they have embraced education at every level, and sought to improve the social, cultural, spiritual, and yes, political quality of the nation in ways that are primarily responsible for virtually everything that is good where the United States of America is concerned.

Nonetheless, recent events suggest that a critical mass of people has concluded that the nation’s elites are violating the social contract. This mode of thinking is frequently expressed as anger at bankers, politicians, members of Congress, and, of course, Wall Street “fat cats.” As indicated, the Occupy Wall Street movement is a manifestation of this sentiment.

The belief that the nation’s social contract is being systematically violated, and that the economic and political systems are rigged in favor of elites, has acquired enhanced urgency and broadened credibility in the past few years, primarily because of lingering effects from the recession.

The crippling financial burdens that have become common among members of the middle class due to the recession may well be the factor most responsible for legitimizing, and mainstreaming, the broadly shared belief that major reforms are in order. Many of those who share this belief had, up until recent times, considered themselves solidly middle-class, and exempt from financial distress of the sort commonly experienced by the poor.

They were undoubtedly influenced in their thinking by the rhetoric of permanent success and prosperity inherent in the messages flowing from the mainstream news and entertainment media.

Thus, when the first victims of the current financial catastrophe were identified as largely blue-collar workers and typically poor and ignored members of racial and ethnic minority groups, the common consensus was that they were responsible for their plight because of assumed personal shortcomings. Once the misery spread to the middle class in the form of job layoffs, depleted unemployment benefits, short sales and depleted 401K accounts, people began to adopt more balanced and sophisticated critiques of the nation’s economic and political systems.

This led to the surprisingly large number of relatively comfortable, middle-class people participating in the Occupy Wall Street movement. Their emergent consensus is that the nation’s wealthy elites are systematically violating the nation’s social contract, and that major reforms of an unprecedented nature need to be implemented in order to set things right.

It is too soon to ascertain what the recommended reforms will turn out to be, and whether they will have revolutionary ramifications. Nonetheless, it is already abundantly apparent at this early stage in the process that this nation’s economic elites are in for the fight of their lives, a fight that a critical mass of the other 99 percent of the population has come to believe it cannot afford to lose.