by Claire Isaacs Warhhaftig

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n just one instant in 1965, I decided to travel to Selma, Alabama, and march for voting rights for African-Americans who had been disenfranchised for decades in the South.

As I plan my return to Selma this year on March 3 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of this historic event, I ask myself: When did I start this journey, and why? And I recall the discrimination in society that was obvious even to a teenage girl.

I was a senior in high school in 1949. Dad said that since he had business in various places that summer, why not all travel together and cross the country?

First stop: Tulsa, Oklahoma. Riding the bus, I noticed black people were gathered in the rear. This naïve California girl thought they preferred to sit together. Then I noticed they weren’t even talking with one another. That evening, I learned that Tulsa had curfew laws. Blacks were prohibited from leaving their homes after 8 p.m. The exception was to work serving a white family, and required a permit.

My next encounter with segregation’s ugly visage was in Nashville, Tennessee’s train station, with its two sitting rooms. The “whites only” space was reasonably clean, regularly painted and offered comfortable chairs. The “colored only” waiting room was one fifth its size, unpainted for decades, and featured splintered benches. I tried not to imagine the restrooms.

We journeyed on to visit our cousins, Julius and Mervin Blach of Birmingham, Alabama, for our first visit ever. Brothers Julius and Mervin owned department stores in various Southern cities, specializing in men’s’ wear. The downtown store was later to be seen as an unfortunate background to notorious Sheriff Bull Connor’s water-hosing of civil rights marchers there.

Our cousins’ wives, Patsy and Lillian, served up hospitality Southern style, day by day. Their country club offered this California girl the chance to show off my Pacific Ocean-honed swimming style. As I climbed out of the pool dripping profusely, 16-year-old cousin Dale and her dry, sun-basking friends cooed, “Whoa, Cuzin Cleah, yoooo sweeeumm!”

But serious menace lurked behind this placid scene. A black family had moved in too close to the white enclave, and their new home was bombed.

Julius, head of his local American Legion chapter, spoke out against the bombing. He had not suggested that the neighborhoods integrate. No. He had simply stated that such violence was wrong. For this stance, he was receiving daily death threats. My father kept this from me until we had left Birmingham.

Back in San Francisco, I did my best to offer companionship to Lowell High School’s single black student. Daughter of the distinguished, Harvard-educated minister of the Unitarian church, Dr. Howard Thurman, she was determined to benefit from San Francisco’s outstanding public college prep school.

The Thurman’s tiny home in the Fillmore district revealed a beautiful, tasteful living style within a shabby Victorian in one of the few neighborhoods where African Americans could rent.

Miss Thurman didn’t make it to my graduation tea, that 1950’s traditional party hovered over by doting aunties and grannies who poured the liquids and served tiny treats. But another black friend, Sylia Baquié of Washington High, accepted. The very next day I was “disinvited” from other Lowell girls’ teas.

Relationships between black and white people in those days were tentative, hesitant. But my Mom managed to form social relations at work in the civil service — the non-discriminatory welfare department — with the brilliant and handsome Elzie Wright. Elzie provided my first exposure to a black adult woman with whom one could joke and enjoy intellectual disagreements.

At Pomona College, the only exceptions to the all-white student body in the 1950s were the occasional foreign students. such as G’nai G’nuk, a girl from Turkey. As a remedy, the college arranged a student exchange with Fisk University in Tennessee. The two black students from Fisk attempted to shrink quietly into the body of the college masses.

Graduate school in Columbus, Ohio, provided an entirely different social matrix. Before I had even left San Francisco, the Dean of Women of the Ohio State University office sent me a brochure listing sororities as specifically “Gentile,” “Jewish” and “Negro,” illustrated in photographs.

Even the local off-campus coffee shop reflected this tripartite divide, catering to each one of these three groups, and woe to anyone who set foot in the wrong territory. Many black students originated from border states like Kentucky to the south. They were unaccustomed to mixing with white people. My only black pal was a UCLA student from Los Angeles.

During World War II, thousands of African Americans from many southern states settled in the Bay Area. Many occupied homes in San Francisco’s Fillmore District vacated by Japanese-Americans sent under guard to “relocation” camps “for the duration” of the war.

The Fillmore neighborhood became a mecca for black culture and entertainment, yet was considered too inappropriate for white girls like myself to get off the B and C streetcars running through that area.

I noticed that one never saw people of color in clothing advertisements. I reasoned that if black models were seen in ads, their presence might become normal and comfortable in daily life. Thus, newspaper columnist Herb Caen made much of the appearance one day in Liebes’ Department Store of pretty young Chinese girls, traditionally garbed, operating elevators. Before this startling development. it was usual for all non-white people to remain unseen in the back of a shop.

In the spring of 1965, news of civil rights struggles erupted in the press and media. The nation roared with anger as they watched people in Alabama brutally attacked by policemen mounted on horses charging with billy sticks and tear gas. The police used this violence against unarmed, peaceful citizens to prevent them from marching from Selma to the state capital in Montgomery to demonstrate for voting rights. The film “Selma” accurately portrays the struggle.

Public reaction was not unlike that after 9/11 in New York, with saturated coverage of the outrage on every channel.

In San Francisco, I joined the protest march from the Embarcadero to Civic Center. It was led by the great orator and liberal Bishop James Pike of Grace Cathedral. From the steps of City Hall, Bishop Pike thundered forth: “I’ve been there, and friends, we need more bodies down there — more bodies, and especially more white bodies.”

So, in that instant, I knew I would go to Selma, Alabama.

My journey began in the Macedonian Baptist Church on Sutter Street in San Francisco. Leaders from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) preached the philosophy of nonviolence and taught us physical self-protection moves. I felt a tap on my shoulder. Seated behind me sat the minister of the Pentecostal church directly across the street. He handed me a small, red, velvet bag, and asked me to present this to someone in Selma, “because none of us can go. Please go there for us.” Filled with nickels and dimes earned by San Francisco’s janitors and chamber maids, this token was a sacred trust I acquired due simply to my place among the pews.

Our group was led by Bill Bradley, a former army sergeant and local activist. He organized our trip, preparing us to deal with both disapproval and danger. The southern-accented stewardesses on Delta Airlines scowled at us. Entering the old Atlanta air terminal, we were greeted by the whisper, “Selma, Selma, Selma,” echoing menacingly around the circular structure. Our canteens, jeans and backpacks had evidently signaled our destination.

After staying overnight in a black church and engaging in more practice in nonviolence, we boarded our bus to Selma. Our five-hour drive led us along a very narrow, two-lane highway with red soil on the shoulders and an abundance of wet, green vegetation, bushes and trees. Passengers new to the South were startled by the reality of signs warning, “Whites only” and “Colored stay out.”

I recall one memorable mental snapshot: Two farmers, a man and wife, dressed in overalls, holding a hoe and a shovel, standing side by side along the road’s edge. A living enactment of Grant Wood’s iconic painting, “American Gothic”? No, not those sour-faced Midwesterners, but a black couple wary of showing any expression, yet curious about these strangers passing by.

We arrived in Selma in the late afternoon, and were deposited directly in front of the famous Brown Chapel of media attention. We got off and heard a man outside shout, “These people, they come all the wa-a-ay from San Francisco! Sa-a-an Fra-a-a-anci-i-isco, folks. Let’s cheer them off the bus!” We hadn’t done anything, but clearly, just our arrival raised spirits in Selma.

Inside the chapel, organizers assigned our sleeping quarters. The young men would sleep on the chapel’s pews. Older people and women were assigned to various local homes. Our hostess, Mrs. Lee, endured a week of nearly 20 folks sleeping on every available horizontal surface in her tidy one-bedroom house. However, this good-natured woman reveled in the excitement of meeting people from everywhere — Chicago, Los Angeles, Cleveland, St. Louis, Denver, Boston, New York.

To obtain food at her home, she, like others in Selma, relied on volunteers who traveled miles away to purchase and deliver it. Activists were boycotting local businesses, including groceries. We scraped up all the money we were carrying to give her. But she was most amused at the packs of trail mix our group carried. She then prepared delicious southern-style food for us.

Each day began with gatherings in a packed Brown Chapel, with hundreds outside on the sidewalk. Speakers from many groups addressed us, leading us in short prayers, welcoming newcomers and thanking all those present. Then, they summed up news of the town’s reactions to recent activities, explained the strategies for new actions, and shared the progress on obtaining permission to march.

We were holding our collective breaths, awaiting the word to march. But the leaders surprised us with a new tactic. Instead of massed short marches into town, we would spread out all over town, and “drive the cops crazy” by picking up folks from all over Selma.

I partnered with Barbara. We were dropped off in a quiet, white residential neighborhood. As directed, we strolled quietly up and down that block, always remaining on the sidewalk. Soon we heard from inside those houses, the sound of pounding footsteps, slamming doors, ringing phones, and voices raised, “They’re coming, they’re here.” No one came out to talk with us. The good white folk were afraid of a couple of young women just walking on the sidewalk.

Next, we could hear sirens screaming from every direction throughout town. Eventually, a police car screeched to a halt in front of us. The police ordered us to stop walking. Then they rounded up some black clergymen in their black suits and white collars, who were walking on the next block.

We asked, “Are we being arrested?”

The police answered by ordering us to get into the car. We had to sit on one another’s laps, a ploy designed to embarrass all of us.

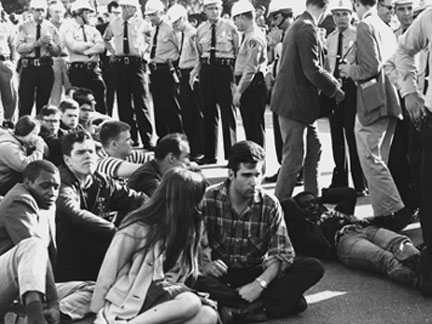

Deposited at the county jail courtyard, we joined about 60 others who already had been picked up. We linked arms and started singing, “We shall overcome.” “Shut up or I’ll bash your heads in!” came the instant reaction. The uniformed officer hollering at us was swinging a billy club that reached below his knees. He was the notorious Sheriff Jim Clark of Dallas County.

We were surprised not to be booked, but were instead loaded into a bus and transported to the black recreation center building. It was in poor condition. Soon the single toilet was overflowing. The drinking water was questionable, the furniture and equipment broken or very overused. I recognized a family friend from New Haven, who worked at Yale. A courteous gentleman, he spread his jacket on the cement floor and invited me to “dinner” — a share of his single roll of Lifesavers.

Time passed. It grew dark outside. We learned that we had given the police a lot of trouble, but the police saved money by not booking us into the already crowded jail. To pass the time, we sang and danced and told stories. Teenaged girls in pink curlers presented their school cheers. Performers from the San Francisco comedy troupe, “The Committee,” led us in improvisations. Ministers prayed with us. Rumors spread that the Klan might bomb us or that we’d be shot coming out. We decided to stay the night.

Some people felt that the men and women should separate. They had heard that rumors were circulating of sexual misconduct among us, and wished to avoid contributing to such nonsensical notions. So, while the men suffered on the downstairs cement floor, I luxuriated on the green felt pool table in the main rec room upstairs, using my jacket as my pillow. The next morning, a messenger delivered the “all clear,” and we marched triumphantly through town to the Brown Chapel.

But there were lighter moments, too. Barbara and I accepted the invitation of some local boys to dance. We drove to the outskirts of town and a huge barn, with dirt floors, great live music, and beer. Folks seemed delighted to see us. And being the first white civilians to enter, we could honestly say we had truly integrated the Selma Sugar Shack!

And then came the announcement: “We are marching today.”

Violence from the police had sabotaged the first march. On March 7, 1965, more than 600 nonviolent marchers were brutally beaten with clubs and whips by Alabama state and local police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, during the first attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery. This police assault became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

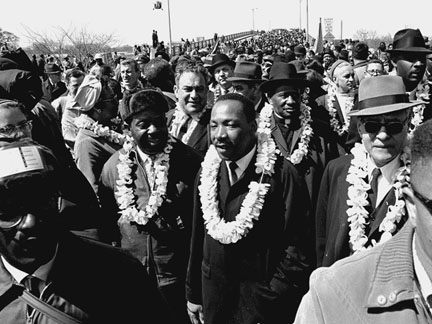

After the nationwide outpouring of negative publicity about the police violence on Bloody Sunday, the State of Alabama finally had been forced to allow the march. On March 21, 1965, the march from Selma to Montgomery began. The police limited the marchers after the first day to about 300. The reason given was the potential for accidents along the very narrow, 50-mile highway.

As we marched over the Edmund Pettus Bridge and out into the countryside, we let out a great cheer. We joked, laughed, linked arms, sang, jogged, and shared food and water. We were so alive.

Yet, there was menace in the atmosphere. The helicopters whirring and buzzing above us caused a breakdown in one marcher, a Vietnam vet. On the sidelines were hundreds of citizens who disagreed with our efforts, and were just staring at us. State troopers bearing rifles and boasting Confederate flags sewn onto their uniforms stood guard along the highway in a decidedly unfriendly stance.

At the end of this long day, we assembled in a large field, but I was unable to spot the train providing transportation back to Selma. Desperate and grubby, I approached a fine limousine with three well-dressed black gentlemen. To give myself courage, I announced, “I’m Claire Isaacs from San Francisco.” To which the gentleman in the front seat replied, “I’m Ralph Bunche from New York.”

Oops! I had just hitched a ride from a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Ralph Bunche had won the Nobel Prize in 1950, and had become active in the civil rights movement. He had joined Dr. King in leading the day’s march out of Selma.

We drove to the very nice home of a Doctor and Mrs. Jackson. My presence seemed to be causing a problem. It was too dangerous for me to walk or ride to my housing by myself at night. Gently, Dr. Jackson convinced Dr. Bunche that he and his chauffeur must drive me to where I was staying. Reluctantly he agreed.

I could see Dr. Bunche’s mood turn dark as we drove through the poorest section of Selma. Asphalt streets were replaced by dirt roads, while street lights and greenery had disappeared from the landscape. At the railroad crossing, we were trapped by the rapid approach of an oncoming train. There was neither safety gate nor lighting there. I hunkered down into the car’s floor. As two black men and a white woman in the same car, we could have been attacked.

When we arrived and I dismounted, I screwed up my nerve to ask Dr. Bunche, “Do you think there will ever be a real brotherhood between black and white in America?” His lips tight, he answered, “I’m not interested in brotherhood. I’m interested in respect,” and drove off.

Because “brotherhood” had been the constant theme of the Selma gathering, I was quite hurt. Over the years, I came to understand the deep meaning of his words. Would there be so many beatings and killings of young black men by white police if respect between races was universal?

Well, it was time to go. I could not wait for the Montgomery demonstration. I had a job and a family at home. Our farewell was a wonderful banquet of real Southern cooking held by local residents for us. With an appropriate speech I presented that little bag of coins to the lady of the house, a community leader.

Upon my return home to San Francisco, I was invited by that Pentecostal church to share my Selma experiences. Garbed in splendid, gold-trimmed, blue satin, the pastor introduced me as “that lady who went to Selma for us.” The congregation, ladies in immense, flowered hats and gentlemen in fine black suits, sat expectantly. Interrupted by intermittent shouts of “Praise the Lord,” “Say it, Sister,” and “Thank you Jesus,” I managed to get through my little talk. What an experience for a nice Jewish girl like me. Amen.

I am returning to Selma this year in March. The amazing coincidence is that a contact at the Selma Chamber of Commerce put me in touch with a Jawanda Jackson. During our first phone conversation, I realized that this Jawanda Jackson is the daughter of the Jacksons who had been kind to me so long ago. What a revelation! We became immediate friends. She has invited me to stay with her and to share in the special events planned for this 50-year anniversary. These include a kick-off dinner by the mayor of Selma.

As we talked, I finally understood why Dr. Bunche hesitated to leave the house and give me that ride. Dr. Martin Luther King was expected at any moment. Together they were to dine, plan the next day’s march, and sleep over at the Jacksons. It was indeed momentous. Now, Jawanda is turning the home into an historic house. I have museum experience, and I am already sharing my advice with her.

After marching in Selma, I felt I had changed. It was not that I became more politically or socially active. I had changed inside. Despite a moral upbringing and good liberal education, I believe it is almost impossible to completely escape the poison of prejudice. It permeates our society.

But gradually I realized I was less likely to feel nervous at the approach on the street behind me of a young black male. I found I could exchange serious thoughts and memories, rather than platitudes, with black women my age. Instead of struggling to connect, I was connected.

No decision is truly instant. For me, the decision to go to Selma was not only to change and repair our democracy, but to change and grow myself.

How pleased I would be to hear from any of the people who made the trip to Selma in 1965. Contact Claire Isaacs Wahrhaftig at cniw@comcast.net