by Ace Backwords

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]aul “Blue” Nicoloff was a really good guy. He was generally liked and respected by almost everybody on Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue scene. The problem was, he never seemed to really like or respect himself.

He dragged himself around town like his body and soul were a terrible burden to him — which apparently they were. When Blue killed himself, we were all shocked, but none of us were surprised.

He often talked about killing himself. A few years ago, when he got on a HUD housing program, he told me: “My lease is up for reapproval after two years. So every day, I save up one of my meds. And if they kick me off after two years, I’m going to swallow them all.”

Blue suffered from some weird form of spiritual anorexia. He seemed to deny his soul nourishment. He was the kind of guy that, if nine good things happened to him it wouldn’t mean anything to him, but the one bad thing that happened would cut deeply into his soul. And stay there forever.

He once said to me: “I vividly remember every bad thing that’s ever happened to me. I remember things from the second grade where I made a mistake and the kids laughed at me. It still hurts me today.”

His mind had this weird editing machine that ran every painful scene back and forth in front of his eyes. Endlessly. He largely trained his razor-sharp, critical mind on himself and sliced himself up into ribbons. Why? Who knows. Karma?

He tried many things to break free from his unrelenting depression, most notably Prozac, seeing a psychiatrist, and drinking lots of beer. Nothing seemed to make a dent in it. Finally, he just gave up, and spent years holed up in his apartment, watching television from the moment he got up until he went to bed. Trying to endure his life as best he could.

What made it all the more disturbing was that he seemed to have so much to live for. He was enormously talented, with that razor-sharp mind of his. Bright. Funny. Opinionated. His opinions alone — endlessly stated, on every subject — were a work of art in themselves.

He was a master of the New Yorker-style, single-panel gag cartoon, only better. His work was not only brilliantly funny — in a dry, clever, cerebral sort of way — it was also highly conceptual. He had a unique way of looking at things, of putting the pieces together, and that was a reflection of his very original mind.

Every month I avidly looked through the Berkeley Monthly, and when I saw they had printed one of Blue’s comics I would look forward to showing it to him: “See, Blue! Look! The world wants you.” Hoping to instill in him a sense that perhaps Blue should also want the world. But he never did. He just never seemed to like this world.

His chronic and endless state of depression seemed to engulf him in a gray cloud of heaviness that he could never quite shake. He would look at you with those big, dark, haunted eyes that burned into you like smoldering coals, but that mostly seemed to look inward and burn into his own soul.

He always seemed to be in the midst of a horrible spiritual battle. That he was losing. He would sit in the window seat of the Cafe Intermezzo drinking his Anchor Steam beer, and his face would reflect such misery and suffering that folks passing by would stop and come in and say, “Cheer up, man.” But there seemed to be no cure for the psychic agony that tormented him.

I first met Blue back in 1994. I was sitting on a bench on Sproul Plaza and this gaunt, emaciated, crazed-looking, street person came up and introduced himself. He was dressed in torn rags, no socks, with the hollow, sunken eyes of a concentration camp survivor.

It turned out he had subscribed to my newsletter years ago when he was a cab driver in Austin, Texas (his last job). He was just a name on my mailing list. And now here he was in front of me. He said that Berkeley seemed sort of interesting from my newsletter, and he couldn’t think of anything else to do. So here he was.

He said he had been sort of watching me for a whole year before he got up the nerve to introduce himself — which was typical of Blue, for he put a lot of thought into everything he did, often with the most convoluted reasoning.

He presented himself largely as a total loser. “I’ve totally given up on life. Which is why I’ve been homeless for the last year. I just don’t care anymore.” But as we walked through the campus towards Shattuck I remember him looking me in the eye, with those haunted eyes of his, and declaring, “I’m a genius, you know!”

He was certainly right out of central casting for the modern-day Van Gogh/tormented-artist role. Only, inexplicably, his cartoons came out light and funny in spite of his dark, dark world view. Of course, he had a loathing for pretension and artifice that prevented him from playing out the artiste role. Mostly, he presented himself to the world as this plain, unassuming, almost Jack Webb-ish, nothing-but-the-facts-ma’am kind of persona.

But he was aware of the great pool of talent within him, talent that he never quite completely harnessed — primarily due to the crippling depressions that seemed to suck the very life out of him. But the few bits and pieces of artwork that did squiggle out into the world hinted at this deep reservoir of creativity within him.

After a couple of years of being homeless, Blue got on SSI and got himself a cheap room at the Amhurst Hotel. Typically, he didn’t take the room with the window view of Shattuck, but a cramped, dank, windowless, little cave in the middle of the floor. Blue denied himself at every point in his life.

It was at this time, during a six-month period of manic creativity, that Blue cranked out most of the cartoons that the world has seen. As his floor piled high with empty beer cans, garbage and cigarette butts, Blue toiled away every day at his professional drawing board. Almost immediately he met with “success” in terms of selling his work to different publications. But it never seemed to translate into anything but the most fleeting happiness. For Blue, any “success” was merely a temporary postponement of inevitable, devastating failure.

Typically, the period ended with Blue concluding that he was no good, that he had no talent, and he destroyed all of his “worthless” cartoons, throwing the original art into the garbage.

Blue was a complete extremist in his outlook. In his mind it was all or nothing.

“Ninety-five percent of everything is crap,” he would say. The remaining five percent he considered completely brilliant. And he had a deep awe and respect and reverence for the artists, writers, and performers who could produce these rare, jewel-like works of perfection. The problem was, he could never sustain his “I’m-a-genius” inclusion into the five percent, and he would plummet helplessly into the scrap heap of the 95 percent.

What doomed him most of all was his outlook. He felt the world was basically meaningless. To Blue, the universe was nothing but mindless atoms and molecules banging against each other, pointlessly, like billiard balls, for no rhyme or reason. It was this dreary, heavy, existential outlook that seemed to drag him down most of all.

During a famous exchange on our Free Radio Berkeley radio show, Blue said: “I don’t think life means a damn thing. What man does is he gives meaning to things. They don’t have inherent meaning.”

We responded: “You mean it’s not discovery, it’s invention?”

“Exactly,” he said.

“So you feel life is meaningless and we just project meaning onto it that’s not really there?”

“I’m positive of that, in fact.”

“So that’s what you MEAN?”

“Yes, that’s what I mean.”

“Get it?”

But he never quite got it. To his dying day, Blue invested great meaning in his projection, ironically enough, that life was meaningless.

His nickname on the radio show was The Take Umbrage Man. And he was ever ready to gleefully jump on, and savage, the slightest falsehood or pretension. In truth, his aggressive, belligerent attack mode was his transparent attempt to build some kind of armor to protect himself, to appear tough and hard, when in fact he was painfully soft and hypersensitive.

Many times after the radio show on the walk home, Blue would slip back into his ever-rejected persona: “I know nobody wants me to do the show.” And I’d have to try and convince him, yet again, that he was great. To know Blue was to walk on eggshells around him, for he was ever ready to interpret the slightest hint of criticism as a devastating personal rejection. After which you wouldn’t see him for six months or a year.

Considering this built-in, self-defeating mechanism that doomed everything he tried, plop artist Richard List pointed out: “The amazing thing isn’t that he killed himself, but that he managed to last as long as he did.” For the mere act of existing, of facing another day, took a monumental, even heroic, effort on Blue’s part.

Despite his dark outlook, Blue had a great sense of humor and laughed loudly and from the belly. I remember one radio show when we played Rodney Dangerfield albums. Rodney droned: “I have a terrible sex life. Terrible. Are you kiddin’? Why, I wouldn’t get any sex at all if it wasn’t for who I am (pause)… A rapist.” Blue laughed and laughed until tears flowed. Blue had a cheeky love of the outrageous, of anything that went beyond the norm of acceptable good taste. He relished saying things that would shock and unsettle. Perhaps because he, himself, was so shocked and unsettled by life.

After a beer or six, Blue would often slip into his “us-Irish-guys-like-to-drink-and-fight” mode. Though he was from a fairly soft academic/suburban background near Boston, and the only boy in a family of sisters, he took a certain pride in his willingness to stand up for himself and “mix it up.” But he was equally famous for never having won a single fight. He almost seemed to delight in his victimhood.

Blue often told, with relish, the story of the time he got into it with fellow Irish brawler, one-legged Dan McMullen:

“Danny’s drunk in his wheelchair and he gets into a fight with this guy on Telegraph. I’m a little drunk myself so I try to break it up. And Danny launches himself out of his chair at me. That’s when he broke my arm. Then he bites me on the leg. He’s literally hanging from my leg with his teeth in me. And I’m hitting him on the head trying to pry his teeth off of me. And it was at that point that a passerby walked by and looked at me with disgust and said: ‘You shouldn’t hit a man in a wheelchair.’”

Blue would tell this story gleefully, with a smile on his face and a belly-laugh of delight. And he would deliver the punchline with the impeccable timing of a natural stand-up comedian. It was the absurdity of it all, and the misconstrued meaning of it all, that inspired his sense of humor — and his comic art — most of all.

During the last year of his life, Blue had a short period where he seemed to finally be getting his life together; a pattern he would repeat many times, but never be able to sustain. He met a wonderful young woman in a chat room on his computer. With his considerable wit he was able to charm her into coming out and visiting him. Soon, they were making plans to be married and Blue seemed happier, more self-assured, than I’d ever seen him as he showed off his “fiancee.”

I didn’t see him for several months. Then one day, he sat down at our vending table on Telegraph Avenue.

“It’s over,” he said, matter-of-factly. He sat there, sort of crying silently, though no tears came out. I don’t think I ever saw Blue cry. It was more like he was shuddering and grimacing from an unbearable inner pain. We talked for several hours, and it was a wrenching conversation, knowing full well the shaky ground he was on. He told me he had tried to kill himself a few days earlier, that he had swallowed several hundred of his pills. But it only knocked him out for about 10 hours. And here he was.

I tried to find the words that would get through to him; that would make him see that he was great, far greater than he could possibly imagine; that life was in fact great and meaningful and magical and amazing and a precious gift; that there was a whole world out there just waiting for him to claim it. But it was as if I was talking in a foreign language. It didn’t penetrate. He could understand the concepts intellectually, but he couldn’t feel it. And yet, even then, in his darkest hour, I remember Blue responding with genuine belly-laughs at my feeble attempts to use humor to lift his spirits.

Even then, he could still delight at the absurdity of it all. For, in fact, his sense of humor was the tiny little life-raft that he clung to all his life, amidst the raging seas of his stormy soul (I can hear Blue from the next life sneering: “Cornball!” at my “stormy soul” analogy). Perhaps that’s why his sense of humor was so brilliantly honed: He needed it so badly.

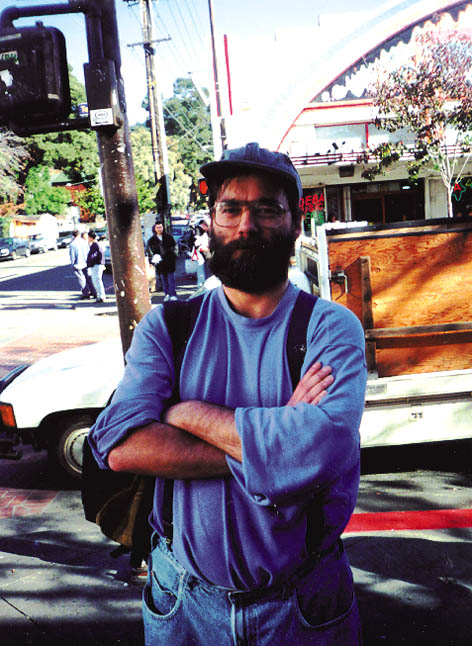

In the next few weeks, we left many phone messages for Blue and wrote several letters (never answered). Finally, we managed to entice him to come up to the Avenue and take some photographs for a yearly calendar we publish. (Did I mention Blue was a brilliant photographer?) He did come up to the Ave, but he was so discouraged he went home after 10 minutes.

That was the last time we saw him. He simply just did not want to live any more.

When we got the news that Blue had committed suicide, we all went through the changes you go through when that happens. What can you really say? We all miss him. We all wish him well in the Great Beyond. Good-bye, Blue.