Interview by Terry Messman

Street Spirit: What led you to make Martin Luther King’s vision of nonviolent movement building such a central part of your activism and your life?

Kazu Haga: I took my first two-day training in Kingian Nonviolence in the fall of 2008 from Jonathan Lewis when I was living in Oakland. We were both working with an organization called The Gathering for Justice founded by Harry Belafonte. Kingian nonviolence was to be one of the core strategies for that group.

So I took the workshop from Jonathan and I told him at the time that this philosophy was something that I always knew but just didn’t have the language to articulate. Jonathan Lewis had already been working with Bernard Lafayette for about 10 years at that point.

So after I took that training, it was weighing heavily on my mind, and then about two months later, Oscar Grant was shot. [Editor’s note: Grant, an African-American man, was fatally shot by BART police officer Johannes Mehserle in the early morning on New Year’s Day 2009 at the Fruitvale BART Station.]

I ended up on the steering committee of the Coalition Against Police Executions (CAPE) which was doing all the mobilizations after the shooting. This philosophy of nonviolence was really heavy on my mind during that whole campaign and I started to see how the anger and, at times, the hatred within the movement was starting to impact our work. The internal dynamics of our movement were starting to have an effect on the external impacts of the campaign.

I started to see how a movement that’s largely driven by anger ultimately kind of eats itself up. What happened internally in the movement is that there was a lot of turmoil within the organizers and a lot of arguing and friction that really tore the Oscar Grant movement apart. The steering committee of CAPE eventually just collapsed because of that internal turmoil.

I also started to see how a lot of the anger which was righteous anger — and everybody clearly had a right to be angry — was being targeted straight at Johannes Mehserle. I felt like this was an issue that was so much bigger than Mehserle, and the more we focused on Johannes Mehserle, the more we were letting the system off the hook. As one of our strategies, we can hold Mehserle accountable as an individual, but also attack the larger system that creates people like Mehserle.

Spirit: The analysis of nonviolent movements is to resist the injustice of an oppressive system, rather than simplistically targeting individuals.

Kazu: Always, individuals are not the enemy. Injustice is the enemy. And it’s not about any one individual, but it’s about being able to develop strategies that address the root of the injustice. I always say that if it wasn’t Johannes Mehserle, it would have been another cop. That’s just the way the system works.

Spirit: Since then, you and Jonathan Lewis have become leaders in the Positive Peace Warrior Network. What is the long-term vision of the Network?

Kazu: It’s an organization that is trying to create a culture of long-lasting, positive peace through the institutionalization of nonviolence. We believe that a lot of our social movements today focus on how to create policy change and structural change. That’s really important and we need to train ourselves so we can do that better.

But ultimately, it’s a cultural shift that we need in this country. You can create the best system of governance that you can possibly create, but if the culture of the people is so corrupt, then they are going to corrupt that system. So our long-term goal is not only to train people in how to change policy, but also how to change cultures and how to reprioritize our values as a society.

Our training really addresses both of those things. It addresses how to build sustainable movements that create long-term, systemic change, but also how to change how we relate to each other as people, how we handle the conflicts that are internal to our families and to our movements. It’s really about changing that culture of violence. It’s not just a system change. It’s not just a policy change. It’s also a cultural change.

Spirit: Many people embrace nonviolence as a tactic, but not as a way of life. Is your commitment to nonviolence a tactical commitment or a way of life?

Kazu: It’s absolutely a way of life.

Spirit: Why?

Kazu: Because what we need in this country is not just a change in our form of government, or a change in certain policies, but also a shift in values. We need a shift in how we respond to the conflicts in our lives. I think one of the problems is that we continue to justify the use of force and violence and fear and intimidation to make the changes that we want to see.

That’s not just a tactical question. It’s a moral question. It’s an ethical question. It’s a question about our principles as a society, and our values as a society. And to shift that, we need to be committed to nonviolence in a far deeper way than just how we’re going to act when we’re out in the streets protesting.

It’s about how are we going to relate to each other as a people, and how are we going to respond to the conflicts that we may have between communities and between individuals. Until we address that question, we can continue to argue all we want over tactics, and over how to change policies and systems. But at the end of the day, we need to figure out how we can relate to each other better as human beings. To me, that’s a question of principles. It’s not merely a question of tactics.

Spirit: Is it true that you left the Peace Development Fund to pursue nonviolent organizing full time? What was your role there and why did you leave that job?

Kazu: I was at the Peace Development Fund for 10 years in their San Francisco office. Before that I had worked in their main office in Amherst, Massachusetts. I was the program director so I was overseeing our grantmaking program and I also managed several of our capacity-building initiatives which meant working with a network of organizations providing them with grants and trainings.

Spirit: So why did you leave?

Kazu: For me, it was really that I saw the potential of Kingian Nonviolence ever since I took that first training. We get this same comment a lot from people that go through our workshops. From the moment I took this training, I knew this had huge potential and this philosophy had to get out there to more people.

Spirit: What was so eye-opening about the new insights you learned from your first Kingian training in 2008?

Kazu: I gained such a better understanding of the way conflict works in our society — both on an interpersonal level, as well as social conflicts like police violence — and really such a better sense of how it is that we can move through those conflicts in a way that is actually effective.

One of my favorite quotes is by Marcus Raskin. Raskin said that the opportunity for revolutionary change happens in the blink of an eye, and if you miss those moments, it’s gone. [Editor’s note: Raskin was a founder of the Institute for Policy Studies and an early opponent of the Vietnam War. He was indicted with Dr. Benjamin Spock and William Sloane Coffin for conspiracy to aid draft resistance.]

I felt like the Oscar Grant movement and the Occupy movement are moments when we could push for radical change — but our communities aren’t prepared to capture those moments. I see the Kingian Nonviolence sessions as training our communities so that when these opportunities happen, we’re ready to mobilize, we have a long-term analysis and we build long-term strategies, and we have a better sense of what needs to happen internally within the movement for it to be successful.

I’ve just been part of so many campaigns that weren’t able to capture those moments, and that’s really a shame.

Spirit: Can you describe the vision and strategy of Kingian Nonviolence?

Kazu: The way Kingian Nonviolence has been handed down to us is that it’s essentially Dr. Martin Luther King’s final marching orders. He had a conversation with Dr. Bernard Lafayette before he was assassinated and he said the next movement they had to lead is to “institutionalize and internationalize nonviolence.”

For all of us doing Kingian Nonviolence work, I think our goal is to ensure that Dr. King’s legacy is alive with us, so that when that bullet was fired into his chest, they missed the target. King had a vision that this philosophy that he was starting to develop could be effective not just in the struggle against segregation, but also in the struggle against militarism, in the struggle against economic injustice, and in how we deal with any sort of conflict as a society.

The more we can prepare people to lead these movements, and the more we can give people an understanding of how to respond to the conflicts in our lives and in our society, the closer we can get to King’s vision of the beloved community. It’s about keeping that legacy alive and educating more people about how we can deal with conflict in an effective way.

Spirit: What does King’s vision of the beloved community mean to you?

Kazu: It’s a community that has justice for all people, and where all relationships have been reconciled. As much as I love the 99% framing in the Occupy movement, I think that’s not a framing that King would have ultimately supported, because our vision of the beloved community includes a reconciled relationship even with those we call the 1% right now. We need to recognize that there are members of the 1% that are supportive of Occupy, as well as members of the 99% that are not supportive.

So it’s never about pointing the finger and saying, “Those people are the problem,” as much as recognizing the injustice in that situation, and saying, “That’s the problem.” And how can we address the injustice while winning over more friendships with the group that we’ve considered to be the enemy. So the beloved community is the 1% and the 99%. It’s the community of East Oakland and the Oakland police department. It’s the Iraqi citizens and the U.S. citizens — everyone having come to some reconciled process so we can live in a balanced world.

Spirit: What role, if any, did Bernard Lafayette play in your becoming involved in nonviolent organizing? Did you ever go through trainings with him?

Kazu: Dr. Lafayette is the coauthor with David Jehnsen of the Kingian nonviolence curriculum, so I met him indirectly when I met Jonathan Lewis.

[Editor’s note: In 1990, David Jehnsen and Bernard Lafayette published “The Leaders Manual — A Structured Guide and Introduction to Kingian Nonviolence: The Philosophy and Methodology.” It has been called the most authentic educational and training text about King’s philosophy and strategies of nonviolence.]

Right when the Oscar Grant movement was going on, I felt instantly that if I could articulate better the philosophy of Kingian Nonviolence and really pass those lessons on, then we could have a more effective movement. So that summer, I attended the two-week summer institute that is held every year at the University of Rhode Island. This is where people come to get trained to become certified trainers in Kingian Nonviolence.

Spirit: Isn’t the University of Rhode Island where Dr. Lafayette originated a peace and nonviolent studies program?

Kazu: Yes, he set up what is called the Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies there. I went there and I studied under Dr. Lafayette for two weeks — two weeks of 14-hour days. Before taking this training, I used to think, like a lot of people, that nonviolence was essentially about turning the other cheek and not throwing a punch. But obviously we were not going to spend 100 hours exploring different ways to turn the other cheek [laughing].

So as a result of this session, I really understood the depth of the philosophy of nonviolence. I had the opportunity to spend those two weeks learning from Dr. Lafayette and I’ve since had the opportunity to train with him on several occasions in different communities.

Spirit: How did this intensive study of nonviolence affect you on a personal level?

Kazu: For me, as a Japanese person that grew up in Massachusetts, it’s amazing to now feel like I’m part of the continuing legacy of Dr. King’s work. Sometimes I’m doing a workshop in a jail, or I remember one time I was doing a workshop with some kids in Selma, Alabama, where King worked, and I was amazed at how I ended up in that position — talking about King’s legacy to a bunch of kids in Selma.

A lot of times what happens with youth development work is that, in an effort to empower young people, and to tell young people that they’re the leaders of today, you lose the connection with the elders. So the message is that young people can do it on their own, and they don’t want or need the elders — and I vehemently disagree with that.

Spirit: Why do you disagree? In activist circles, we tend to almost idolize the role of youth in building movements.

Kazu: I think that people like Dr. Lafayette have learned so much — both what worked and what hasn’t worked — and I think it’s our responsibility to learn from them and to continue their legacy so that we can take our struggles one step further than what they did.

You know, I’ve kind of come to terms with the fact that the idea I have of the beloved community is not something that I’m going to see in my lifetime, and I’m okay with that. Which means that my role is to get up as close as we can to that vision so that the next generation can take it a little bit further and the generation after that can take it a little bit further.

It’s like a relay race. So in that sense, we have a responsibility to learn everything we can from the past generation so that we’re not starting where they did, but we’re starting where they left off. So it’s always a privilege for me to work with and learn from our elders in that way.

Spirit: The vision and strategies of Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign in 1968 seem very close to the Occupy movement led by young activists.

Kazu: Absolutely.

Spirit: What major parallels do you see between these two movements and what are the differences?

Kazu: A lot of people don’t know this, but in the last speech King gave in Memphis the night before he was assassinated, he was actually calling on people to move their money out of big banks and move it into local financial institutions.

In the Poor People’s Campaign, they were organizing the Resurrection City and they were calling on poor people all over the country to come camp out in Washington, D.C. That encampment was to be used as a hub of operations to shut down the entire city. So I think, tactically, there are a lot of similarities with Occupy.

Later on in King’s life, he really started seeing the ties between racial injustice and economic injustice, and really was seeing how poor people throughout the country are impacted in very similar ways. I think that’s what the Occupy movement was also trying to show, is that regardless of where you live in the country, regardless of what race you are, we’re all impacted by these economic policies.

When the housing bubble popped, a lot of people started to see that it wasn’t just poor Black communities that have had to deal with these issues forever, but that, at any given moment, they could also be impacted by these issues as well. So that’s when you started to see the solidarity between all the different classes and the different races so that all the different communities started to come together in Occupy.

There are also some major differences between Occupy and the Poor People’s Campaign — some major differences.

Spirit: What are the major differences?

Kazu: The idea that Occupy was a leaderless movement and how decentralized it was. That was very different from how they organized in the civil rights movement where they had very clear leadership and they also had very clear goals. That’s one thing that campaigns in the civil rights movement were always very strategic about: being able to articulate very clearly the specific goal for each campaign.

Without specific goals, it’s hard to build strategies and figure out what tactics are best to use. In Occupy, we spent a lot of time talking and arguing about tactics, and that created a lot of division in the movement. But we never even agreed on what the goal was. And tactics are something you use to get to a goal. So we were putting the cart in front of the horse, essentially, in arguing over tactics before we agreed on what the goals were. I think that was one of the main faults of Occupy and one of the main differences between the civil rights movement and Occupy.

Spirit: The Poor People’s Campaign was based on organizing in poor communities all over the country, and mobilizing poor people to speak for themselves and act for themselves. But in Occupy, poor and homeless people often didn’t feel welcomed and certainly were not given the central place of honor that King intended.

Kazu: Yes, I agree. I think that was one of the other dangers of that 99% framing, because the 99% is a big umbrella and there’s a lot of power dynamics within that 99% that I don’t feel were properly addressed. Yeah, within Occupy there were always a lot of conversations about how to bridge that gap.

But I think because a lot of these issues were something that a lot of communities of color and low-income communities had already been dealing with for hundreds of years, so when different people started to speak out around Occupy issues, a lot of low-income communities were looking at it like, “Where have you all been?”

So now, when people within Occupy were asking why aren’t poor people and communities of color coming to the general assemblies, I think a lot of it has to do with why weren’t the folks that are active in Occupy involved in East Oakland and West Oakland beforehand. A lot of the homeless people that were sleeping in the camps were sleeping in camps before the Occupy camps started, and where were we in helping them when they were already feeling this repression?

There’s a need for folks to really look at that history — a long history of colonialism and racism and injustice that have gone on for a long time in this country, from the founding of this nation. And without acknowledging that history, it’s hard to ask, “Well, why aren’t the poor people here?”

Spirit: A forum was held in Oakland at a moment of great controversy to discuss the two different directions confronting Occupy — nonviolence versus the diversity of tactics. In looking back now, what was significant about that forum?

Kazu: Well, I don’t know if we were successful in doing so, but one of the most important things about that forum was that we were really clear from the start that we didn’t want to frame it as a debate. It was a dialogue to get to better understand each other’s perspectives. I think that’s essentially what we still need to do.

Obviously, I’m opposed to things like property destruction. But I really do believe in a dialogue with the people that are advocating those tactics. If they defined the vision of the society they’re trying to create, and I defined the vision of the society I’m trying to create, I’m pretty sure it would be very similar.

So I think we really need to learn to identify what we have in common, as opposed to focusing constantly on where we differ. There are some real differences in ideology, in tactics and strategy. But if we can’t first have the conversation about where we agree, we’re always going to be arguing with each other, because we have no baseline level of trust.

One thing we were trying to do at that event was to offer both perspectives so that even if folks disagreed with our perspective, at least they could understand it — and vice versa. Within the nonviolent movement, there’s often a tendency to rush to judgment anytime anyone identifies as an anarchist or even mentions that they believe that property destruction is a legitimate tactic. I happen to disagree with that, but that shouldn’t automatically make me believe that they’re an enemy to the movement or that there’s no way we can work with them.

One goal of that event was to try to bridge that gap. Yes, we have differences and let’s really articulate where our differences are, but let’s also realize that we’re all trying to build the same movement.

Spirit: During the controversy over tactics in Occupy Oakland, you took a visible public role in advocating nonviolence. Did you take heat for that stand, and, if so, what did that feel like?

Kazu: Absolutely, I took heat. Being an advocate for nonviolence in a place like Oakland, I’ve developed a really thick skin. I was taking a lot of heat ever since the Oscar Grant movement for advocating for these things. I think a lot of it has to do with misconceptions about what nonviolence is. But I’ve been booed, I’ve had things thrown at me, a lot of negative online posts and things like that [laughing].

I’ve really had to learn to ignore Facebook discussion groups and online debates because I really feel like that’s one of the main culprits of some of the divisions within Occupy — Facebook discussions and online discussions.

Spirit: Why do you think online discussions tend to worsen these divisions?

Kazu: Well, because I think human beings communicate with a whole lot more than just words. I think that things like tone and eye contact are so essential to our ability to communicate and understand each other, and when we take that away and we have these discussions on Facebook and the Internet, we say things to each other that we would never say to each other in person.

Spirit: That’s because it’s called Facebook, but it’s really faceless.

Kazu: Right, right [laughing]. It’s anonymous, and so I think it’s really dangerous. I’ve never seen a conflict successfully resolved through Facebook. Because the general assemblies weren’t a place that was conducive to real dialogue, people turned to Facebook to try to hash out differences, and I think that’s one of the worst places you could possibly try to do that.

Spirit: What does it feel like to be attacked when you’re just trying to do good work for a cause you really believe in?

Kazu: Well, I’ve grown a really thick skin. And I understand that a lot of the people that criticize me, first of all, are doing so without a good understanding of what it is I’m actually advocating. But I also recognize that for every person that booed me, there’s ten supporters out there, and my focus really has to be on them.

I think that anytime anybody speaks out for anything, you will have haters. Anytime you have success with anything, anytime you take a stand for anything, you’re going to have haters. Anytime you take the lead for anything.

I remember Martin Luther King talking about all the dozens of death threats he would get all the time. It just comes with the nature of the work. Whether I’m taking a stand for nonviolence, or for the diversity of tactics, if I’m having success with my work, there’s going to be people who criticize me. My focus has to be on the people that actually want to work with me.

Spirit: What do you make of the argument for diversity of tactics, as espoused by some in the Occupy movement?

Kazu: Well, first of all, I think that way of framing things is completely off. There’s so much diversity within nonviolence that I think this argument between “nonviolence versus diversity of tactics” is completely wrong. Starhawk made a really good point about this conflict of diversity of tactics: Without some baseline agreement of what we’re not going to do, then how far are we allowed to take it? Does that mean that we would legitimize torture, for example?

Spirit: If we just blankly endorse any diversity of tactic imaginable, does that even allow for assassination?

Kazu: Right. I’m sure that people who are using black-bloc tactics wouldn’t agree with a lot of those things, so I think both sides can agree there’s some limit to it. But the advocates for diversity of tactics really didn’t allow for that conversation to take place. Also, with a lot of the advocates for diversity of tactics, the anger that kind of guides some of their work is righteous anger and I think it’s important to acknowledge that.

I would almost rather see people out there breaking windows than people sitting at home doing nothing, and seeing all the injustices of the world and saying, “That’s not my problem.” At least they’re taking a stand and really putting their bodies on the line. So I think it’s important to acknowledge those things that we do share in common, because one of the complaints that a lot of advocates for nonviolence get is that we’re not out on the streets risking our bodies. I think we need to acknowledge the courage they do have, but be able to talk to them and have real dialogues about the differences in strategies and how those different strategies impact our movement.

Spirit: Do you think that the property damage we’re talking about — the rock-throwing and window-breaking and starting fires in downtown Oakland — is responsible for the divisiveness and loss of support that consumed Occupy Oakland? And, if so, do you believe the loss of public support caused by these actions is irreparable?

Kazu: Well, the first question: Yes, absolutely. Whether or not you agree with property destruction, the property destruction did help contribute to the loss of public support for our movement. When you’re able to remain nonviolent even in the face of police violence, that paints a very clear picture of who is right and who is wrong.

There’s a big difference between the images that we saw of the students at UC Davis who were getting pepper-sprayed and who were sitting there nonviolently, and the violence that happened at Occupy Oakland. That public narrative is a really powerful weapon for us, when we can show people that we are standing nonviolent and claiming that we’re on the right side of justice. But when we engage in property destruction, then that narrative gets really complicated.

When we use militant tactics — whether those tactics are nonviolent or violent — then we need the support of the public. Because those who have the courage and the ability and the privilege to use those militant tactics — again, whether the tactics are nonviolent or not — are always going to be in the minority. There’s always going to be those frontline soldiers in any movement who are willing and able to use those tactics. So if the people who are willing and able to use those tactics are in the minority, then they need the support of the majority, or else it’s just never going to work.

So, back to your question. Absolutely, the property destruction in Oakland led to a decrease in public support and that decrease in public support is ultimately what has hurt this movement the most.

Spirit: What happened to the great hopes sparked by the Occupy movement and where is the movement now headed?

Kazu: One of the things I’ve been thinking a lot about is the fact that after the end of the Montgomery bus boycott and the beginning of the lunch counter sit-ins, which was the next major campaign of the civil rights movement in the South, there was a four-year lull.

So I think we’re in that lull right now, and the potential to gain that momentum is still there — as long as we’re active in between, and we don’t look at the lull and say, “Oh, the movement is dead,” and we just give up. I think as long as we keep moving, and as long as we keep organizing, and as long as we keep evaluating our past successes and failures, I do think that the potential for this movement to become reborn, if you will, is definitely there. We’ve just got to be really strategic about how we’re moving forward in this time.

Spirit: How do you understand what happened with the civil rights movement in that interval between the end of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956 and the student sit-ins at lunch counters in 1960? What did civil rights activists do during those four years?

Kazu: A lot of what they did was training and strategizing and building networks. And strengthening those networks so that the next time that opportunity came about, they were much more ready to take advantage of it and ride that momentum long-term. For example, one of the most successful lunch-counter sit-ins was one that Dr. Lafayette was involved in down in Nashville. They trained for an entire year before they engaged in those sit-ins.

So what I look at with Occupy is what types of trainings are we doing to ensure that the next time people are trained to do this? I think that the idea that we’re sending people into the streets to fight for justice and face potential police violence without being trained at all is dangerous and ludicrous. Social change does not come easily. People need to know what they’re doing. We need to be building a nonviolent army who are disciplined and strategic and know exactly what needs to happen.

Spirit: What positive things do you think were accomplished by Occupy?

Kazu: One of the things that Occupy did that we’re still benefiting from today is that it woke up so many people. So it’s no longer taboo to say that we’re calling for radical, fundamental changes in this country. That is a huge, huge success of this movement. If we can continue to take advantage of that and continue to work with people who, before this movement, may never have considered doing any sort of direct action, and continue to train them, and continue to strengthen those relationships, and continue to push for some of the analysis around economic injustice that came out of Occupy, I do think we can be reborn as a movement.

Spirit: What did you learn in the course of being involved with the people of color caucus in Occupy?

Kazu: I can only speak from the perspective of Occupy Oakland. The conversation around the names “Occupy” and “Decolonize” pissed off a lot of communities of color. A lot of people of color felt really disrespected during that argument.

Spirit: What led to so many people feeling disrespected?

Kazu: A lot of people felt like the term “Occupy” was not a fitting term for what we were actually trying to do, especially with the really strong presence of indigenous leaders and indigenous activists in the Bay Area. A lot of people felt like our communities have been occupied for so long, that we weren’t trying to occupy our communities. We were trying to liberate our communities. We were trying to decolonize our communities.

In our efforts to reach out to communities of color, it’s all about recognizing the history of what has happened to these communities of color. So a lot of people were advocating changing our name from “Occupy” to “Decolonize.” I think a lot of those disagreements were legitimate and people have every right to believe one way or another. But the tone of the discussions were at times very hurtful and disrespectful to people.

Spirit: All that made it tougher to build a movement that united and included people instead of alienating them.

Kazu: We always say that nonviolence isn’t just a guide for our external actions, but it also has to be a guide for our internal interactions with each other within the movement. There were so many instances where people felt hurt and disrespected and there was just a lot of power dynamics and issues of privilege that came into play that people weren’t recognizing.

Spirit: You give intensive two-day trainings in Kingian Nonviolence and there’s even 40-hour sessions. What in the world can you do to fill up such a long training period?

Kazu: Oh, are you serious?! Two days is never enough for us [laughing]. It’s never enough for us! One of the great things about our workshop is we try to hit at every single learning style. So we do mini-lectures, we do readings, we do videos, we do roleplays and small group work.

This curriculum is ultimately about how to change the world and how to change your relationship to the world. It’s a deep philosophy. The biggest misconception about nonviolence is that it means to not be violent. If you’re simply learning about how to not be violent, you might be able to get a lot of good lessons in a day or two. But learning how to confront violence, and learning how to become the antidote to violence, and the antidote to injustice, is a lifelong struggle.

So we actually say our two-day workshop is not even a training. It’s an introduction to a philosophy which you can be trained in, if you so choose. But it’s really just an introduction to a framework of how to look at conflicts, how to analyze conflicts and how to respond to those conflicts.

Spirit: How many people has the PPWN trained over the past year and what kind of groups have you trained?

Kazu: Coming into this year last January, we had only one two-day workshop scheduled. In the last 11 months since then, we’ve held about 40 workshops of at least two days duration.

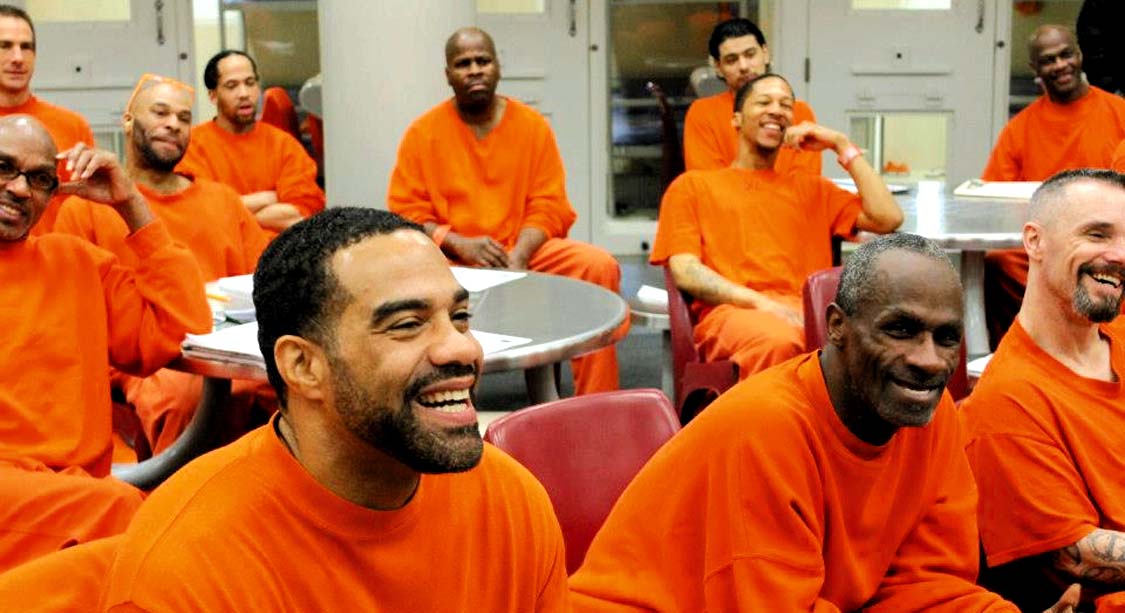

We’ve reached well over one thousand people in the last 11 months between last January and November 2012. About 350 of them have been men and women in the local county jails, about 350 more have been young people of high-school age, and the rest have been in communities all across the country in eight different states.

Spirit: Sally Hindman, the director of Youth Spirit Artworks, said the workshops on King’s philosophy had a life-changing impact on some of the youth that attended. Why do you think it has such an impact?

Kazu: I’m always amazed that there are a lot of those special moments that come from almost every single workshop. I’ve seen it have that impact on young people, and on men and women in prison. I can really identify with it because it was a similar process for me when I went through the Kingian training.

Spirit: How do Kingian trainings affect youth living in violent neighborhoods?

Kazu: We live in a very violent world and for many young people, violence is all they’ve ever known. We were at a workshop once in Chicago when we told a young woman that there were communities even in Chicago where young kids are not getting shot up every day. She just couldn’t believe it because that’s all that she’s ever known.

For a lot of people, when all they’ve ever known is violence, when we offer them an alternative way to deal with their conflicts, it’s something that they’ve never even thought of, because this society doesn’t provide spaces for us to really think about how we’re responding to the conflicts in our lives. We always say conflict itself is a completely neutral thing. It’s how you respond to that conflict that gives it a positive or negative outcome.

As a society, we’re only taught to respond to conflicts in a way that often tends to escalate things. So when we offer people that alternative way, I think it’s a really mind-opening experience — especially for young people, and for men and women in jails and prisons who have never really thought of an alternative. It’s really life-changing for a lot of people.

Spirit: It’s very impressive to me that the Positive Peace Warrior Network holds trainings for people in jails. Not many activists even think about bringing the message of nonviolence to prisoners.

Kazu: When we talk about building a movement or a nonviolent army in the Positive Peace Warrior Network, those men and women in prison are warriors. They have been through so much and are able to cope with so much, and they know more than anybody about the impact of violence and how violence has affected their lives and community.

They know better than anybody how much things need to change. It’s their kids that are out on the streets today having to deal with all that. So in terms of looking for peace activists, the jails are some of the best places to look.

Spirit: Gandhi looked in that same direction, too, by organizing among the Untouchables and by working with military warriors to help build a nonviolent movement. He found they had the courage to express “the nonviolence of the strong.” King trained members of violent street gangs in the tough parts of Chicago as nonviolent marshals in his housing marches. Some might wonder if teaching nonviolence to a captive audience could seem alienating to prisoners. What have those trainings in jails really been like?

Kazu: We’ve done them in San Bruno County Jail and in the Hall of Justice in San Francisco. And they’ve been incredible. What always amazes me is that often, a good half of the participants didn’t volunteer to be there. And they let us know from the very beginning that they are not happy at the fact that they’re there.

Spirit: They were ordered to be there by the prison officials?

Kazu: They were ordered to be there. And when they find out that it’s two consecutive eight-hour days, a lot of them get really upset at us. So that’s often where we start with the day. But in every workshop we’ve done, by the end of it, it feels like the entire crowd has been won over.

One gentleman told us recently that he hates coming to jail over and over and over again, but if he didn’t get locked up this time, he wouldn’t have come to this workshop, so for that time it was worth it.

We’ve even gotten comments from some of the deputies on the staff who kind of sneak up to us after the event is over and say, “Hey, don’t tell the guys I told you this, but even I was listening to what you were saying, and I’m going to practice a lot of what you were telling the guys.”

The last woman’s jail that we went into at the Hall of Justice in San Francisco, there were two women who had a conflict prior to that workshop. So when they saw each other that morning, they really didn’t feel like they could be in the same room.

But after the first day of the workshop, they felt inspired to try to reconcile that conflict. During the closing circle of the workshop, the women embraced with a hug in the middle of the circle. There’s just constant stories like this. And that’s just in two days! So our jail workshops have been going incredibly well.

Spirit: How did you get the idea in the first place that you were actually going to go into jails to do nonviolence trainings?

Kazu: Oh, I’ve always wanted to! If we’re trying to create peace in our communities, we need to reach out to the folks most impacted by violence and injustice. Those are the men and women in the jails and prisons, and in the poorest, dangerous neighborhoods, and those are the folks that often get left out of society.

I feel like if anything is going to change in communities like East Oakland, we need to empower the folks who have been living in those communities, and who have been harmed by some of the policies that created those conditions.

So, to me, if we don’t have leadership from men and women who are getting locked up, men and women who have been homeless, then ultimately, we will never be able to create sustained change. I feel like we need to start there.

Spirit: When Dr. Lafayette spoke here in Oakland on the International Day of Peace, I remember how joyful he seemed at the response of prisoners in San Bruno jail to the presentations on nonviolence. How did those sessions go?

Kazu: I think it was great! Because I don’t know how common it is for someone like Dr. Lafayette to go into the jails to bring programming like that from someone with a big name like that.

I think it’s really important that we are constantly reminding the men and women in the jails that society hasn’t forgotten them, and that we are trying to offer things for them, that we are trying to work with them, and build with them.

I think Dr. Lafayette was pretty impressed with the work we have been doing in there. Because up until recently, almost all our work has been outside of the jails. So for him to be able to go into jail, and to see these guys that have been so inspired by the workshop that he created, I think it’s really exciting for him.

Spirit: Another group that has been marginalized and ignored by society are the youth living in very poor neighborhoods. It seems that the Positive Peace Warrior Network also focuses a great deal of effort on training these young people forgotten by society.

Kazu: Yes, and for important reasons. No movement has been successful in the past without leadership from young people. But also, I recognize that my vision of the beloved community isn’t something I’m going to see in my lifetime. So whatever gains we make during my lifetime, we have to make sure that the next generation is ready to take up the call after my generation is gone.

As long as we’re not investing in our young people, it’s very possible that the gains that we make in our movement are just going to get lost in the next generation. So I think we need to constantly, constantly, invest in our young people.

To read the accompanying article about Kazu Haga and the Positive Peace Warriors Network, click HERE.