by Bonni McKeown

“Somebody has been cashing checks and they’ve been bouncing back on us. And these people, the poor class of Negroes and the poor class of white people, they’re getting tired of it. And sooner or later it’s going to bring on a disease on this country, a disease that’s going to spring from midair and it’s going to be bad. It’s like a spirit from some dark valley, something that sprung up from the ocean…” — Chester Burnett (Howlin’ Wolf)

Howlin’ Wolf offered that profound insight in an interview at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles in 1968. Wolf was a powerful performer and band leader, and one of the greatest and most passionate blues vocalists of all time. One of the most important founders of the blues, he was perhaps a modern-day prophet as well!

In the cotton fields and levee camps of the early 20th century South, African Americans kept on creating their music. In both churches and juke joints, singing held the community together as Jim Crow oppression threatened to keep people confined in a slavery-like caste system. Songs could convey things too dangerous to speak about — long work hours, low pay, and unfair racist bosses.

Blues helped people survive and occasionally to protest. Muddy Waters, Otis Spann, Little Walter and Willie Dixon traveled to Washington to play at the Poor People’s encampment two months after Martin Luther King’s death in 1968.

As Buddy Guy quoted Muddy in a Rolling Stone interview on April 25, 2012: “Blues. The world might wanna forget about ‘em, but we can’t. We owe ‘em our lives.”

Renowned jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, on CBS This Morning on April 6, 2012, said after sitting in at an Alabama juke joint: “Blues are good for the soul. Their rhythms are inseparable from the American identity. They encompass the optimism of American identity. And they’re not naive. Blues tell us bad things happen all the time, and they do, and we can engage with them.”

Marsalis described the friendly, healing atmosphere of America’s hard-to-find juke joints: “Humility is the foundation of humanity … When you reach out to someone, when you’re empathetic, that’s your humanity, when you’re together…. Music brings us together in thought and feeling, and emotion.”

We Need the Blues More Than Ever

Blues is the opposite of exploitation, subjugation and separation of people by rule of fear. Blues insists we’re human, imperfect, yet there’s Spirit in us. We can get it together.

We need blues now more than ever. New Jim Crow snuck up on America and legalized racial discrimination via the War on Drugs.

New Jim Crow has shot the Bill of Rights full of holes and put millions in prison, starting with people who are black, brown, and poor white. At the same time, Mr. Fat Cat has picked the pockets of the 99%.

Because of the grip on the political system by the 1%, federal tax dollars that should be paying off the national debt or building bridges and trains and solar panels are going instead to build more bombs.

The nation’s mayors shut down the schools and mental health clinics, then wonder why our streets are full of crime and sorrow. People with nowhere to turn, often turn violence on themselves and their neighbors.

As people lose jobs, houses and education, the 1% invest in over-policing (including the military weapons brandished in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014) to hold back the rage.

African American members of the lower 99, where the blues comes from, have been subjected to the oppression and lies of the 1% rulers for 400 years. Now more of us are forced to experience exploitation from the same beast.

‘America’s Greatest Contribution to the World’

Blues can’t cure society, but it can get people out of the dumps. Kurt Vonnegut, before his death in 2007, called African American music “America’s greatest contribution to the world … the remedy for a world-wide epidemic of depression.”

Blues grew up from the ground. It’s the root of America’s popular music — gospel, rock, jazz, soul, funk, R&B, hiphop — even part of country music.

Producer and songwriter Willie Dixon often said, “Blues is the root. Other music is the fruit.”

Blues has a call and a response, a rhythm and a swing. The music makes you feel better. Watch a blues audience, eyes half closed, tapping their toes — or in a lively mood, shouting out their comments on the singer’s lines.

Blues can tell any story — happy or sad, scary or funny. It doesn’t solve the world’s problems, but it brings folks together, and that’s a start.

Where to find this healing blues music? Don’t look in the major media owned by the 1%. The music industrial complex doesn’t like to play real blues (or air real news).

Each blues song comes from the heart of an ordinary person. It cannot be mass duplicated and controlled. The blues is freedom. The blues is truth.

How I Found the Blues

Like many fans, I got into blues music to cure my own blues. The Creator blessed me with the personality of an obsessed reformer and writer. As a kid, I haunted the Philadelphia library for biographies of pioneers: Susan B. Anthony, Jane Addams, Amelia Earhart, Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington.

In the fighting pioneer tradition of my father’s Scot-Irish family, I always swam upstream like the heroes I read about. My mother’s grandparents were Russian-Rumanian Jewish immigrants. Some were also known for playing music and occasional political hell-raising.

At 13, when I watched Martin Luther King speak on TV at the March on Washington, I started to understand how unfairly black people had been treated. I wanted to help.

At West Virginia University, studying for my journalism degree, I heard talks by Muhammad Ali and Dick Gregory. I overheard African-American students, clustered at their favorite table in the Mountainlair student union, debate Black Power and music. “You like soul music?” said Ron Wilkerson, one of my college buddies. “You oughta dig Miles Davis. And John Lee Hooker.” Many of the black students had it together. Their teachers in segregated high schools held Masters and PhDs but couldn’t get jobs in white schools. So they had stayed in the community, passing all their smarts to the kids growing up under them.

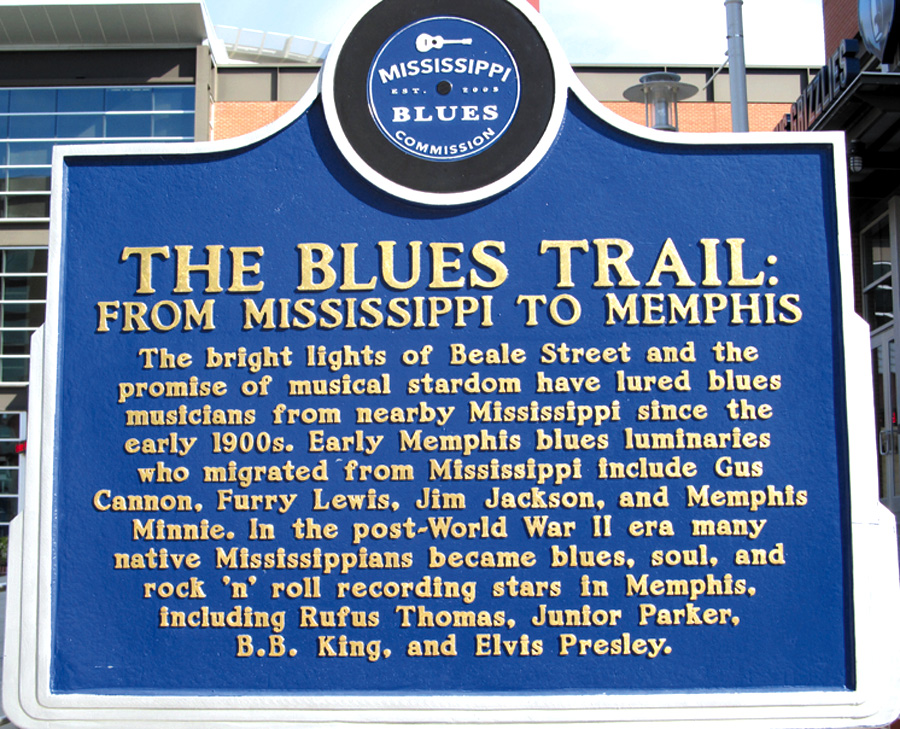

But no sooner than African-American culture began showing its beauty and power, it was driven down again. Not only were urban anti-poverty programs shut off in the late 1960s, but also highways and urban renewal blasted through black business districts. Blues and jazz clubs were bulldozed, from Detroit’s Hastings Street to Beale Street in Memphis and the Triangle District in West Virginia’s own capital, Charleston.

America’s “consumer” economy consumes land and people and culture, replacing everything with manufactured imitations. Cities and streets were named for Indian tribes after the army and the settlers killed them off. Likewise, in many places with “blues” in the name, the music has been killed off and replaced with imitations.

Partly because of my activism, I was forced out of the family business in the late 1990s. Losing my job gave me the blues. I was drawn to the music that had spawned those soul hits I’d danced to in the 1960s. Growing up to Broadway show tunes and Beethoven, I learned a new set of revered names: the blues piano players Roosevelt Sykes, Memphis Slim, Big Maceo Merriwether, Katie Webster, Big Moose Walker, Otis Spann. I took blues piano classes at Augusta Heritage summer blues camp, in my own state, at Elkins, West Virginia. Each year I’d go home, practice with records and tapes, sit in with local bands, and drive occasionally to blues jams in Washington, D.C.

The Destruction of Maxwell Street

In the year 2000, I read on the D.C. Blues Society website that Chicago musicians and fans were calling for help. The city was about to tear down Maxwell Street, the birthplace of Chicago blues. Maxwell Street was the century-old, open-air marketplace where people of all cultures mixed and mingled and shopped and danced. With my daughter gone on to college, I was free to pursue another cause. Maybe a Martin Luther King dream.

I hopped a train for the Windy City. Longtime activist and Roosevelt University professor Steve Balkin, known on the street as “the Fess,” took me to the street’s famous 24-hour hotdog stand. Nearby on a plywood bandstand cobbled by bluesman Frank “Sonny” Scott, musicians played hour after hour for weeks, protesting the demolition: Jimmie Lee Robinson, the lanky “Lonely Traveler” in cowboy boots, and the Queen of Maxwell Street, 80-year-old Johnnie Mae Dunson Smith. The Maxwell Street Foundation website now memorializes the grief and the history (at http://www.maxwellstreetfoundation.org).

By 2002, the wrecking ball had claimed Maxwell Street. The city had ignored our protests. Jimmie Lee, dying of cancer, had taken his own life. But several dozen blues musicians were still playing in Chicago, keeping the spirit alive.

I’d played some gigs as a coffeehouse piano songstress but knew little about playing in a band. Maybe I could find a struggling band leader who’d let me learn, in exchange for my help writing their bio and website.

I returned to Chicago in March 2003. Like they say, it’s a tough town. A clique of younger guys, some black, some white, elbowed my newbie self out of a North Side club jam. They played so fast I couldn’t keep up with their funk and rock. They didn’t want to hear me trying to shadow Otis Spann; they wanted synthesizer sounds. I felt no swing nor groove, just flying fingers and screeching amplifiers more appropriate for rock than blues. I fled the club, wheeling my 88 keys out the door.

Poet and critic Sterling Plumpp, who rose from Mississippi sharecropping to a post office job and then to a professorship in Chicago, stated in Fernando Jones’ book I Was There When the Blues was Red Hot: “My perception is that the White, Yuppie Lincoln Park audience tends to like high-energy music. They think that blues should show some sort of relationship to rock’n’roll. Therefore a great deal of potentially significant Black blues musicians distort what the music is about to please that audience.”

The Blues and Community

So, what is the blues supposed to be about on its home turf? Chicago harmonica player Billy Branch, who started the idea of “Blues in the Schools,” explains community participation to critic David Whiteis in the book Chicago Blues: Portraits and Stories. “It’s call-and-response, how the audience and performers react to each other…. There’s something in the Black experience that defies, probably, definition…. It’s an oral tradition —’Yeah baby!’ ‘That’s what I’m talking ‘bout!’ ‘I hear you!’ ”

That tradition called to me. Real blues is not deafening; it’s not in a hurry. It’s personal. It tells stories. It’s hospitable, even to those from outside the hood.

I decided to test my early piano skills in another tourist club: the Monday night jam at Buddy Guy’s Legends. The wiry, dark-skinned drummer in Jimmy Burns’s band, I could see, was really into it. Totally living in the moment of the music, he drove the group with a crisp and swingy backbeat. A world of expressions from joy to pain flickered across his face. At the end of each line of 12-bar blues, he’d add magnificent little rumbles and flourishes.

The drummer wore a blue-and-red sports jersey and a backwards baseball cap, more in the hiphop fashion than the felt hat and fancy shirt of a bluesman. His wide-set eyes seemed to look in different directions. One eye, I learned later, had been damaged several years ago by a minor stroke that luckily did not affect his hands or voice. Or was it the time he fell off the swing as a little kid and hit his head?

At the end of the song, the drummer came back from whatever planet he was on. With quick, spidery hands, he switched the drums from a left-hand setup back to right-handed for the next drummer. Then he moved to the front of the stage and picked up a microphone. With a nod to the audience, he hummed a musical riff to the guitar player and directed the bass and drums to come in.

The music boiled up into a one-chord trance song, something like John Lee Hooker or Howlin’ Wolf would lay down. The groove reached out like a whirlwind. A huge voice swept through the room, pouring out the pain of his soul and many others. It was as if the great, 6-foot-4-inch, 300-pound Wolf had come back to life and was howling through the singer’s slender frame.

This was no imitation; this was blues. Tourists looked up from their catfish and beer, startled. Then they applauded.

As the band took a break, Jimmy Burns began calling us, the wannabe blues musicians, to the stage. When they called “Barrelhouse Bonni” I sat gingerly at the unfamiliar keyboard and played the chords I’d learned at Augusta Heritage Blues camp in West Virginia. Most of the guitar guys were used to playing with other guitars rather than with a piano, and preferred to drown me out. I was glad people couldn’t hear all my wrong notes anyway. When the song ended, someone tapped me on the shoulder. It was the wiry singer and drummer who had channeled Wolf.

“I like the way you play,” he said. “Not too many folks play piano that way anymore.”

“Thank you,” I said, nearly falling out of my chair. “I’m still learning. I loved your drumming and singing. Who are you?”

He Played with Legends

“I’m Larry Taylor.” He pointed to the band leader. “Jimmy Burns is my uncle. My stepdad was Eddie Taylor. He was on VeeJay and other record labels. Toured all over the world. Played guitar with Jimmy Reed.”

“Wow, you’re the real deal,” I said. Blues, like oldtime Appalachian mountain music, is often passed down in families.

“Yep. I’m a real bluesman. Grew up with it right in my house,” he said. He’d played on stage with legends like John Lee Hooker, Junior Wells, Albert Collins. “The stuff they’re playing in these clubs these days, some of it ain’t the real blues.

“Some of these younger guys, don’t matter if they black, they ashamed of the blues,” Larry explained. “They used to know how to play. But the old guys, a lot of them are gone. And the younger guys, they’ve played the modern style of R&B for so many years they forget how to do the traditional blues. Or they speed it up and play too loud like rock. They act scared of the feelings in the music. Can’t handle it. They play a song fast so they can get through it.”

“Bet you could get a lot of people to come out and hear the real blues,” I said. “The blues societies are always talking ‘Keep the Blues Alive.’ So why don’t you have your own band?”

“I’ve thought about it,” he admitted. “Band leaders are the ones who make money in this business. Side musicians, they just don’t get paid very well.”

I told him my dream of playing in a Chicago blues band and promoting a heritage African American artist.

“I’ve got some tapes of my stepdad playing,” Larry said. “He died back in 1985. Want to see them?”

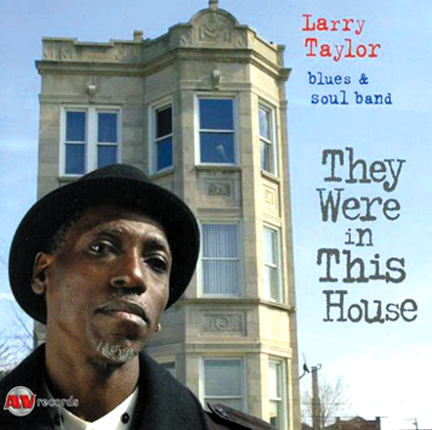

Six months later, Larry Taylor set about forming his own blues and soul band. He’d bring back the forgotten hits of his stepdad’s generation and his own.

Surely promoters would snap up a real bluesman with Larry Taylor’s heritage — a little guy with a big voice, a band leader full of soul and rhythm. Even if I lacked music business connections, I could look up festival and club venues, and send out a bio of Larry and a CD with a few of his songs. His calendar should fill up with gigs in no time!

So I thought. Now it’s been 10 years. Larry is 10 years older, still struggling to raise his kids on the West Side of Chicago, as shots are fired, jobs dry up, drugs are sold on street corners, people are getting shot, and schools and mental health clinics are closing around them.

The urban blues get worse every day — with less music to compensate. Maybe we should have heeded the song by Larry’s former bandleader, A.C. Reed: “I’m in the Wrong Business.”

Is Larry’s music worth promoting? Judge for yourself. (See http://www.larrytaylorchicagoblues.com)

Many other things have contributed to Larry’s blues story and to mine. Whatever mistakes we’ve made in trying to promote Larry, we’re not imagining these obstacles in the business. Jim ONeal, founding editor of Living Blues magazine, spotted them over 20 years ago in his article “The Blues: A Hidden Culture” (Living Blues, March/April 1990).

“The young black bluesman usually finds no easy road to success even when he is heard…. The upper level is narrow and constricted, populated by the veterans who have been there for years. They have the reputations, the recognition, the better recording outlets, the top management, and they have the history. Their gains are hard earned and well deserved, and if they protect their positions by preserving the hierarchy (with the consent and support of the blues audience), it’s understandable.”

O’Neal, now an archivist at Bluesoterica, went on to recommend: “Maybe what is needed most in the new age of blues is a push toward establishing up-and-coming blues talent within the black community, on black radio, in black publications and in black music awards. The black audience for blues is still large, though not particularly well served by radio and the recording industry.”

O’Neal who is white, noted that black DJs seemed content to play old blues and soul records without searching for younger performers of this type of music. Some “southern soul-blues” artists do get played. While the vocals come across with soul, much of their music doesn’t have the same sound; synthesized keyboards can’t replace piano and horns.

Sharing the Pain and Beauty of Life

Heritage blues musicians have the gift of pain and the challenge of sharing it. Their experiences tap into the beauty and the unrealized dreams not only in African-American culture, but in all of human life. They can make us feel what they are feeling, and that bond draws people together. The greatest blues artists are the ones who feel the deepest pain. Because they carry so much pain, they are strong and fragile. Appreciation keeps them going.

Fernando Jones, harp and guitar player and songwriter, points out in his 1988/2004 book I Was There When the Blues was Red Hot, that fellow black scholars sometimes fail to allow their culture to take credit for the blues. The late bass player and blues songwriter and producer Willie Dixon often said, “Blues are the root. Other music is the fruit.”

Blues is famous worldwide, but not always valued in the community. The Blues and the Spirit symposia produced by Dr. Janice Monti at Dominican University since 2008 have made a dent in this, giving Black scholars a chance to address the value of the blues. (See http://www.dom.edu/blues-and-spirit-iv)

Fernando also quotes Chicago Black promoter and politician Ralph Metcalfe: “The reason we (Blacks) shy away from the Blues is because of our self-hatred…. We worship the white man’s gods more so than being concerned with our own heritage and origins. Blues musicians in the beginning were the traveling minstrels. Black educators do not teach this in school because they have not been trained themselves…. At Columbia University I went to the music department; it was filled with Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach (but not) Waters, Wolf and Wells…. Blues is the classical music of black people.”

If the community ignores its blues men and women and does not feel their presence, or lets the world exploit them without feeding their families, they will die off. Not just from a broken heart, rejection and starvation, but from being stifled from sharing their music.

I have seen Larry Taylor’s personal suffering. He has spoken out about these things since before I came to Chicago, and spoke out again in our book Stepson of the Blues. His singing is deeper, his repertoire broader, his rhythm more profound than ever. Since 2008 he has not been hired to perform in Chicago’s annual blues festival, nor hired by a national or international festival.

Meanwhile, some media are saying blues are now a white thing and that’s all there is to it. This is pure B.S. Portraying the Blues without Black people is like portraying my grandmother’s Scotland with mariachi players instead of bagpipers. You can’t keep the blues alive without ongoing generations of live, authentic, professional African American blues men and women studying and playing the classical music of their culture.

The blockage has to end. Their energy has to be released. When it is, everybody benefits. Blues is the music of survival. Life goes on. We all gonna boogie — all night long!

Bonni McKeown is a journalist, activist and blues piano player who supports heritage musicians upholding the blues and soul tradition. She wrote the music section of the Maxwell Street Foundation history website (see http://www.maxwellstreetfoundation.org) and has written a blog “West Side Blues” for the Austin Weekly News. Bonni promoted Larry Taylor and worked with Larry to produce his 2004 debut CD “They Were in This House,” reissued in 2011 by Wolf Records. http://www.larrytaylorchicagoblues.com. She co-authored Stepson of the Blues, a limited-edition autobiography of Taylor, in 2010, and wrote a screenplay, “The Rhythm and the Blues,” based on part of Taylor’s life story. For more informationm see www.barrelhousebonni.com